Letter of Transmittal Shri Shaktikanta Das

Governor

Reserve Bank of India

Mumbai October 26, 2020 Dear Sir, It gives us immense pleasure in submitting the Report of the Internal Working Group set up to Review extant Ownership Guidelines and Corporate Structure for Indian Private Sector Banks. Thank you for the confidence reposed in the Group to look into the various dimensions of such a matter of enormous importance. The Group has approached the entire gamut of issues with an open mind and the final recommendations reflect a practical approach while being cognisant of the prudential concerns. Yours sincerely, Sd/-

(P. K. Mohanty)

Member | Sd/-

Sachin Chaturvedi

Member | | | | Sd/-

Lily Vadera

Member | Sd/-

S.C. Murmu

Member | Sd/-

Shrimohan Yadav

Convenor |

Acknowledgements The IWG expresses its gratitude to the Governor, Reserve Bank of India, Shri Shaktikanta Das, for entrusting the responsibility on the Group to review the extant licensing and regulatory guidelines relating to ownership and control, corporate structure and other related issues in private sector banks in India. The IWG also had the benefit of guidance from Shri M. K. Jain, Deputy Governor. The IWG greatly benefited from the inputs received during the discussions held with various experts. The IWG would like to express its gratitude to former Deputy Governors Smt. Shyamala Gopinath, Smt. Usha Thorat, Shri Anand Sinha and Shri N. S. Vishwanathan for sharing their deep insights with the group. The IWG also acknowledges the valuable inputs shared by Shri Bahram Vakil (Partner, AZB & Partners); Shri Abizer Diwanji (Partner and National Leader - Financial Services EY India), Shri Sanjay Nayar (CEO, KKR India), Shri Uday Kotak (MD & CEO, Kotak Mahindra Bank.), Shri Chandra Shekhar Ghosh (MD & CEO, Bandhan Bank) and Shri P. N. Vasudevan (MD & CEO, Equitas Small Finance Bank). The Group places on record its appreciation for the excellent support and assistance provided by Shri Vaibhav Chaturvedi, Ms. Beena Abdulrahiman and Shri N. Ramasubramanian all General Managers, Reserve Bank of India, for preparing excellent background notes, providing valuable inputs during deliberations and final drafting of the Report. The able assistance from Shri Sooraj Menon and Shri R. Sakthivel, both Assistant General Managers, RBI is also sincerely acknowledged.

Executive Summary 1. Banking sector is a vital cog of any healthy economy. While the sector contributes significantly to the welfare in an economy by providing intermediation through maturity and risk transformations to balance the utility preferences of the economic agents, it is tightly regulated considering the social externalities of the negative spillovers. One of the channels through which regulations ensure that the incentives of the banking companies align with that of the larger society is through having a say in the market structure and organisation of banking business. Licensing regimes, which aim to ensure that only those participants with the right amount of ability and willingness to do banking business in line with the social and economic preferences of a financial system are permitted to organise such businesses, have been a key component of the regulatory arsenal of prudential regulators, including Reserve Bank of India. 2. Prior to nationalisation of banks, Indian banking sector had been organised in the private sector. The sector was opened up again post liberalisation with the first round of licensing of private banks that was done in 1993. Since then there have been two more rounds of licensing of banks in the private sector – in 2001 and 2013 – culminating with the on-tap licensing regime of universal banks since 2016. This period has been interspersed with licensing of differentiated and specialised banks such as Local Area Banks (LABs), Small Finance Banks (SFBs) and Payments Banks (PBs). 3. The provisions and requirements of the various rounds of licensing have not been uniform; in fact, it reflected the regulatory preference and the generally accepted prudential principles as existed at each time. As a result, presently, India has a number of banks working under differing regulatory regimes when it comes to organisation of business. This has the potential to raise concerns about uneven playing field as well as scope for regulatory arbitrage. Moreover, various structural changes have occurred over the years both in the Indian economy as well as the body of banking regulation. For instance, the financial intermediation by banks have come down in relative relevance when compared to the early years of liberalisation – more intermediation is being carried out these days by non-banking intermediaries including capital markets. The prudential regulation has also shifted its preference to a widespread disaggregated shareholding structure for banks as enshrined as Pillar III of the Basel guidelines. Further, the aspirations of the Indian economy for the future also requires a strong and vibrant banking sector to be in place to adequately support the investment demands of such growth, which may require a fundamental rethink of current regulatory stance towards the question of how a banking business should be organised. 4. With the above backdrop, the Internal Working Group (‘the IWG’) was constituted by the Reserve Bank on June 12, 2020 to examine and review the extant licensing and regulatory guidelines relating to ownership and control, corporate structure and other related issues. The IWG, under the leadership of Dr. P.K.Mohanty, senior Director in the Group, focused on the major issues that need to be addressed based on the current experiences of the Reserve Bank and examined the various statutory provisions underpinning the extant norms governing licensing of banks, manner in which the banking and para-banking activities are organised, organisational structure of banks, and those governing ownership and control of the banks. The IWG also interacted with certain serving and retired officials of Reserve Bank, bankers, legal experts, and other professionals and experts in the field of banking and finance to understand their insights and views on the subject. The IWG also studied the international practices followed in some major jurisdictions. 5. After detailed deliberations, the IWG has made the following major recommendations on the various issues that were considered for deliberations: I. Lock-in period for promoters’ initial shareholding, limits on shareholding in long run, dilution requirement and voting rights (i) No change may be required in the extant instructions related to initial lock-in requirements, which may continue as minimum 40 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank for first five years. (ii) The cap on promoters’ stake in long run of 15 years may be raised from the current levels of 15 per cent to 26 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank. This stipulation should be uniform for all types of promoters and would mean that promoters, who have already diluted their holdings to below 26 per cent, will be permitted to raise it to 26 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank. The promoter, if he/she so desires, can choose to bring down holding to even below 26 per cent, any time after the lock-in period of five years. (iii) No intermediate sub-targets between 5-15 years may be required. However, at the time of issue of licences, the promoters may submit a dilution schedule which may be examined and approved by the Reserve Bank. The progress in achieving these agreed milestones must be periodically reported by the banks and shall be monitored by the Reserve Bank. (iv) As regards non-promoter shareholding, current long-run shareholding guidelines may be replaced by a simple cap of 15 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank, for all types of shareholders. II. Pledge of Shares (i) Pledge of shares by promoters during the lock-in period, which amounts to bringing the unencumbered promoters’ shares below the prescribed minimum threshold, should be disallowed. (ii) In case invoking the pledge results in purchase/transfer of shares of such bank beyond 5 per cent of the total shareholding of the bank, without prior approval of Reserve Bank, it may restrict the voting rights of such pledgee till the pledgee applies to Reserve Bank for regularisation of acquisition of these shares. (iii) The Reserve Bank may introduce a reporting mechanism for pledging of shares by promoters of private sector banks. III. ADR/GDR issued by banks The Reserve Bank may legally examine the issue and make suitable regulations so that this conduit is not used by dominant shareholders to indirectly enhance their voting power. The options may include prior approval of the Reserve Bank before entering into agreements with depositories, with a provision to modify the Depository Agreement to assign no voting rights to depositories; and a mechanism for disclosure of the details of ultimate depository receipt holders so that indirect holding may be reckoned along with direct holding. IV. Eligibility of Promoters (i) Large corporate/industrial houses may be allowed as promoters of banks only after necessary amendments to the Banking Regulations Act, 1949 to deal with connected lending and exposures between the banks and other financial and non-financial group entities; and strengthening of the supervisory mechanism for large conglomerates, including consolidated supervision. RBI may examine the necessary legal provisions that may be required to deal with all concerns in this regard. (ii) Well run large Non-banking Financial Companies (NBFCs, with an asset size of ₹50,000 crore and above, including those which are owned by a corporate house, may be considered for conversion into banks provided they have completed 10 years of operations and meet the due diligence criteria and satisfy the additional conditions specified in this regard. (iii) With regard to individuals and entities/groups, the provisions of the extant on-tap licensing on universal banks and SFBs are appropriate and do not warrant any change. However, for Payments Banks intending to convert to a Small Finance Bank, track record of 3 years of experience as Payments Bank may be sufficient. V. Initial Capital (i) The minimum initial capital requirement for licensing new banks should be enhanced as below: -

For Universal banks: The initial paid-up voting equity share capital/ net worth required to set up a new universal bank, may be increased to ₹1000 crore. -

For Small Finance Banks: The initial paid-up voting equity share capital/ net worth required to set up a new SFB, may be increased to ₹300 crore. -

For UCBs transiting to SFBs: The initial paid-up voting equity share capital/ net worth should be ₹150 crore which has to be increased to ₹300 crore in five years. (ii) As the licensing guidelines are now on continuing basis (on-tap), the Reserve Bank may put a system to review the initial paid up voting equity share capital/net-worth requirement for each category of banks, once in five years. VI. Corporate Structure – Non-operative Financial Holding Company (NOFHC) (i) NOFHCs should continue to be the preferred structure for all new licenses to be issued for Universal Banks. However, NOFHC may be mandatory only in cases where the individual promoters / promoting entities / converting entities have other group entities. (ii) Banks currently under NOFHC structure may be allowed to exit from such a structure if they do not have other group entities in their fold. (iii) While banks licensed before 2013 may move to an NOFHC structure at their discretion, once the NOFHC structure attains a tax-neutral status, all banks licensed before 2013 shall move to the NOFHC structure within 5 years from announcement of tax-neutrality. (iv) The Reserve Bank should engage with the Government to ensure that the tax provisions treat the NOFHC as a pass-through structure. (v) The concerns with regard to banks undertaking different activities through subsidiaries/Joint Ventures (JVs)/associates need to be addressed through suitable regulations till the NOFHC structure is made feasible and operational. The Reserve Bank may frame suitable regulations in this regard inter alia incorporating the following and the banks must be required to fully comply with these regulations within a period of two years. -

The bank and its existing subsidiaries/JVs/associates should not be allowed to engage in similar activity that a bank is permitted to undertake departmentally. The term ‘similar activity’ to be defined clearly. -

If a group entity desires to continue undertaking any lending activity, the same shall not be undertaken by the bank departmentally and the group entity shall be subject to the prudential norms as applicable to banks for the respective business activity. -

Banks should not be permitted to form/acquire/associate with any new entity [subsidiary, JV or Associate (>20% stake – signifying significant influence or control)] or make fresh investments in existing subsidiary/JV/associate for any financial activity. Investments in ARCs may be as per extant norms. -

However, banks may be permitted to make total investments in financial or non-financial services company which is not a subsidiary/JV/associate upto 20 per cent of the bank’s paid up share capital and reserves. VII. Listing Requirements (i) SFBs to be set up in future: Such banks should be listed within ‘six years from the date of reaching net worth equivalent to prevalent entry capital requirement prescribed for universal banks’ or ‘ten years from the date of commencement of operations’, whichever is earlier. (ii) For existing small finance banks and payments banks: Such banks should be listed ‘within six years from the date of reaching net worth of ₹500 crore’ or ‘ten years from the date of commencement of operations’, whichever is earlier. (iii) Universal banks: Such banks shall continue to be listed within six years of commencement of operations. VIII. Harmonisation of Various Licensing Guidelines (i) Whenever a new licensing guideline is issued, if new rules are more relaxed, benefit should be given to existing banks, immediately. If new rules are tougher, legacy banks should also confirm to new tighter regulations, but transition path may be finalised in consultation with affected banks to ensure compliance with new norms in a non-disruptive manner. (ii) As and when the changes in certain norms, as recommended by the Group in this report are accepted by Reserve Bank, these should be made applicable to existing banks also, in the manner as prescribed in previous paragraph. (iii) As the licensing is now on-tap, Reserve Bank may prepare a comprehensive document encompassing all licensing and ownership guidelines at one place, with as much as possible harmonisation and uniformity, providing clear definition of all major terms. These guidelines may be equally applicable on legacy or new banks. This may be updated from time to time depending on emerging requirements. 6. The detailed rationale underpinning the above recommendations and the details of the various deliberations undertaken and the viewpoints that were considered during the process of finalising the above recommendations are discussed in the ensuing chapters.

Chapter 1 : Introduction 1.1 The banking sector in India has evolved over the past three decades into a more diverse, competitive sector with the entry of several new players at various points, reflecting the policy orientations at specific times. The key turning point was in 1993 when, as part of the broader reforms in the financial sector, fresh licences were issued for a few private sector banks as part of the new licensing policy. The process has continued, with the fresh licences being granted for universal banks in terms of the guidelines issued in 2001 and 2013. 1.2 The broad policy relating to ownership and control in Indian private sector banks is guided by the framework issued in February 2005. Though the overarching principle that the ownership and control of private sector banks should be well diversified and that the major shareholders are ‘fit and proper’, have remained unchanged, the specific contours have evolved over the years with specific prescriptions given as part of licensing guidelines issued at various points in the past. The guidelines for on-tap licensing of universal banks, issued in 2016 and the for small finance banks (SFBs), issued in 2019, capture the extant norms. 1.3 However, the fast changing macroeconomic, financial market and technological developments portend newer opportunities to transform the banking landscape. In alignment with the agenda set for the economic growth of the country to become a $5 trillion economy, there are heightened expectations for the banking sector to scale up for a greater play in the global financial system. It was in this context that, in order to leverage these developments for engendering competition through entry of new players, the Reserve Bank initiated the process for a comprehensive review of the extant guidelines on licensing and ownership for private sector banks. This exercise would also provide an opportunity to harmonise the norms applicable to banks set up under different licensing guidelines to ensure a level playing field and foster competition among these banks. 1.4 Accordingly, on June 12, 2020, an Internal Working Group (‘the IWG’) was set up by the Reserve Bank to examine and review the extant licensing and regulatory guidelines relating to ownership and control, corporate structure and other related issues, with the following members: -

Dr. Prasanna Kumar Mohanty, Director, Central Board of RBI -

Prof. Sachin Chaturvedi, Director Central Board of RBI -

Smt. Lily Vadera, Executive Director, RBI -

Shri S. C. Murmu, Executive Director, RBI -

Shri Shrimohan Yadav, Chief General Manager, RBI – Convener 1.5 The Terms of Reference (TOR) of the IWG were as under: -

To review the extant licensing guidelines and regulations relating to ownership and control in Indian private sector banks and suggest appropriate norms, keeping in mind the issue of excessive concentration of ownership and control, and having regard to international practices as well as domestic requirements; -

To examine and review the eligibility criteria for individuals/ entities to apply for banking licence and make recommendations on all related issues; -

To study the current regulations on holding of financial subsidiaries through non-operative financial holding company (NOFHC) and suggest the manner of migrating all banks to a uniform regulation in the matter, including providing a transition path; -

To examine and review the norms for promoter shareholding at the initial/licensing stage and subsequently, along with the timelines for dilution of the shareholding; and, -

To identify any other issue germane to the subject matter and make recommendations thereon. Approach of the Committee 1.6. The IWG was led by Dr. P.K.Mohanty, as the senior Central Board Director in the Group. The IWG was cognisant of the enormity of the task at hand and went about its work in a structured manner, identifying the key issues that needed detailed examination. The IWG also examined the relevant statutory norms contained in Banking Regulation Act, 1949 [particularly amendments carried out through Banking Laws (Amendment) Act, 2012], Companies Act, 2013, Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) regulations, etc. to understand the legality and remit of certain provisions contained in guidelines/regulations issued by the Reserve Bank from time to time. 1.7. The IWG interacted with certain serving and retired Deputy Governors of Reserve Bank, serving bankers, legal experts, and other professional and experts in the field of banking to get their insights on the subject. A summary of views of experts on various issues is furnished in Annex I. The IWG also studied the international practices followed in some major jurisdictions. These interactions and research greatly helped the IWG to frame its views. Structure of the Report 1.8. The Report is structured into four key chapters, apart from the Introduction. Chapter 2 discusses the broader context for the need for review of the licensing and ownership guidelines. Chapter 3 traces the evolution of the licensing framework for private banks. Chapter 4 provides an overview of international experience. Chapter 5 contains discussions on the diverse perspectives regarding each of the identified issues and the final recommendations of the IWG.

Chapter 2 : Macroeconomic Environment and the Structure of Banking System 2.1 India has been one of the fastest growing economies over the past two decades, notwithstanding the severe shocks during the period. Average Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of India, which slumped after the Global Financial Crisis from 8.2 per cent in 2009-11 to 5.3 per cent in 2011-13, moved upward from 2013-14, reaching 8.3 per cent in 2016-17, which is considered to be one of the longest cyclical upswing in the post-independence period. Though the fundamentals of economy remained strong, India’s real GDP growth showed signs of slowdown since 2017, accentuated by cyclical global downturn which commenced in 2018, with the GDP growth slowing down to 4.2 per cent in 2019-20. The current financial year has been marred by the impact of Covid19 pandemic and the IMF has projected the global growth at −4.4 percent in 2020. For India, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) estimates the real GDP growth in 2020-21 to be negative at (-)9.5 per cent. However, the recovery process has commenced and as per MPC estimates, the real GDP growth for Q1:2021-22 is expected to be 20.6 per cent. The IMF, as part of its latest Word Economic Outlook (October 2020) has projected India to register a growth of 8.8 per cent in 2021, which would be the highest among all major economies.1 2.2 Looking beyond the recovery phase over the near term, it may now even be a greater imperative to review and address any structural issues in the financial sector to ensure that it is in a position to provide the necessary growth momentum to the economy. Undoubtedly it will require many other pieces to come together for a sustained growth push, but given the criticality of the banking sector it may be an important determinant in this regard. To support its growth and to fulfil its aspirations, India needs an efficient banking sector. 2.3 This chapter provides an analytical overview of the present structure of the banking system in India. Structure of the Banking System 2.4 The evolution of Indian banking has been dotted with many discontinuities that reflect quite conspicuously in the structure of the sector today. The sector is today characterised by a fragmented market composition with different categories of banks in existence with varying ownership patterns. Reforms in various areas have altered the market structure, ownership patterns, and the domain of operations of institutions, and infused competition in the financial sector. The gradual liberalisation over the last few years has allowed private participation in the sector and eased entry of foreign banks. The existing banking structure in India is multi-layered with various types of banks catering to the specific and varied requirements of different sections of society and economy. Chart 2.1 captures the key transformative reforms in this regard: An Assessment – Global Comparison 2.5 The banking sector has grown significantly over the years but the total balance sheet of banks in India still constitutes less than 70 per cent of the GDP, which is much less compared to global peers, particularly for a bank-dominated financial system (Chart 2.2). 2.6 An important indicator of bank-based financial deepening, that is, private sector credit, has expanded rapidly in the past five decades thereby supporting the growth momentum. However, the domestic credit provided by Indian banks still remains low compared with major emerging market and developing economies (EDEs), and advanced economies (Charts 2.3 and 2.4).

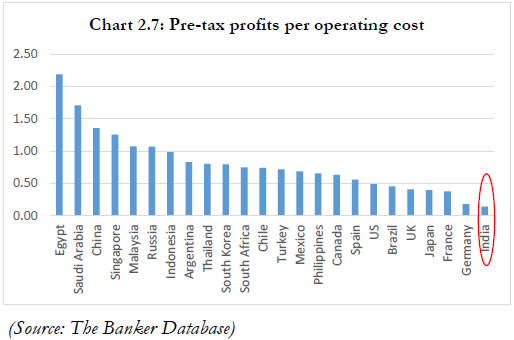

2.7 At present only one Indian bank is in the top-100 global banks by size. As on December 31, 2019, in the list of top-100 global banks by asset size, Banco de Sabadell, a Spanish bank, with total assets of $251,408.59 million (approx. ₹18 lakh crore) was at the hundredth position. In comparison, the top five Indian banks had the asset size as depicted in Table 2.1: | Table 2.1 | | Bank | Total Assets (₹ Crore)

(as on March 31, 2020) | | State Bank of India | 39,51,394 | | HDFC Bank Ltd. | 15,31,498 | | Bank of Baroda | 11,61,648 | | ICICI Bank Limited | 11,04,168 | | Axis Bank Limited | 9,19,303 | | (Source: RBI) | 2.8 It may be instructive to note that in terms of number of banks, as well as the total size of the banking system, India ranks in the top decile globally among the 158 banking systems tracked as part of The Banker database. However, the average Tier 1 capital of banks in India at $ 4.92 billion (approx. ₹37,000 crore) as of March, 2019 is less than most of the global peers (Chart 2.5). 2.9 The Indian banking sector cannot be said to be highly concentrated. The Herfindahl Hirschman Index (HHI) for India is around 0.08 for both credit and deposits which indicates an unconcentrated industry. The share of five largest banks in India is one of the lowest as compared to other jurisdictions. (Chart 2.6). 2.10 However, in terms of cost efficiencies, Indian banks are just at the bottom of the list, primarily on account of large staff costs. The net pre-tax profit generated by the Indian banks per unit of operating costs is just around $ 0.14 million (approx. ₹1 crore) as against a global average of $ 1 million (Chart 2.7).  2.11 While there may be multiple reasons for the relatively small size of the banking system in India as compared to other countries, which may be a matter of separate study, it does seem that part of it has to do with the structural economic setting in which the banks operate. The confluence of various factors over the past decades including inefficient credit allocation; high interest rates; weak credit enforcement mechanisms; absence of viable resolution mechanisms; operational inefficiencies of several banks, etc. can be said to have contributed to the stunted growth of the banking system. The problem of scale is not something unique to the banking system. As reported in a recent Bloomberg article, “As much as 40 per cent of the country’s listed nonfinancial firms have revenue of less than $15 million. They’re tiny even by emerging-market standards, and the ratio hasn’t increased at all over the past decade.”2 The two may in fact be closely interlinked. 2.12 The experience after the 2008 global financial crisis also highlights the problems of forced credit expansion. The huge credit allocation to the infrastructure sector, with its attendant structural problems, is considered prime reason for the accumulation of large, unresolved stressed assets on banks’ balance sheets. This was one of the major factors constraining the credit creation capacity of banks in the ensuing years. While the enactment of Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) in 2016 and the new resolution paradigm pursued by the Reserve Bank can be said to be game changers in this regard, it may be a while before these structural changes translate into a sustained positive impact on lending. 2.13 While select private banks have been able to buck the trend and have shown healthy, sustained growth over the years, they have some way to break into the global top-100. Thus, in order for the banking sector to play a greater role in the economic growth, it would be imperative for the underlying ecosystem to also change. Several policy measures taken/being taken in this direction are undoubtedly a huge positive and much will depend on how these changes play out over the coming years. The role of the private banks will, though, be crucial. Domestic Context - Increasing role of Private Sector Banks 2.14 The private sector banks have evolved since 1990s and play a major role in the banking business in India. As may be observed from the following chart, credit in the banking sector registered higher growth after the banking sector was opened for competition through licences granted to private sector banks in 1994. It establishes the important role being played by private sector banks in the growth of the economy. 2.15 A comparative position of private sector banks, PSBs and foreign banks (FBs) on certain important parameters since 2000 is given in Charts 2.9 and 2.10 which show the growing importance of private sector banks.

2.16 As may be seen, the contribution of private sector banks towards deposits and advances of Scheduled Commercial Banks3 has increased from 12.63 per cent and 12.56 per cent in 2000 to 30.35 per cent and 36.04 per cent respectively in 2020. The PSBs have been consistently losing market share to the private banks, a process which has markedly hastened over the past five years. The primary reason for this has been the beleaguered balance sheets of PSBs on account of the non-performing asset (NPA) overhang of post-global financial crisis years. 2.17 Private banks, particularly new generation private banks, also score over the PSBs in terms of the operational efficiencies. 2.18 This may also be a reflection of the difference in their business models. The risk-weight density of private banks is discernibly higher than PSBs, at the same size of loan book relative to total assets, which indicates higher risk appetite on the part of private banks (Chart 2.13). However, a much lower gross NPA ratio and smaller pool of written-off accounts gives them a much cleaner balance sheet for more productive utilisation of capital. 2.19 The above differences also reflect in the market valuations of the two sets of banks. Most of the big private banks enjoy a Price (P)/Book Value (BV) of more than 1, which indicates their attractiveness for fresh market raising (Table 2.2) Table 2.2 Price to Book Value of major banks

(as on October 20, 2020) | | Banks having P/BV > 1 | P/BV | Banks having P/BV > 1 | P/BV | | Bandhan Bank | 3.3 | Axis Bank | 1.55 | | Kotak Mahindra | 4.7 | ICICI Bank | 2.1 | | HDFC Bank | 3.6 | Yes Bank | 1.33 | | IndusInd Bank | 1.27 | IDFC First Bank | 1.03 | | RBL Bank | 0.85 | SBI | 0.83 | | (Source: Financial Express) | 2.20 Therefore, capital has really not been a problem for private banks. During the last five years, private banks have been able to raise an aggregate capital of ₹1,15,328 crore from the market (through follow-on public offers, qualified institutional placements, American depository receipts/global depository receipts, employee stock option scheme, etc.) as compared to ₹70,823 by PSBs, which needed a massive infusion of another ₹3,18,997 crore from the GOI (Chart 2.14). 2.21 As may be seen, the total capital held by private banks has reached almost par with PSBs at a much lower balance sheet size. Conclusion 2.22 As is evident from the analysis above, the increasing share of private banks has provided the system with a requisite robustness. The recent merger of PSBs as part of the Government’s plan to have a few large banks have given size to some of the PSBs. While private banks have had their share of problems, some of them have grown significantly. Going forward, there may be space for both PSBs as well as private banks, existing as well as new, to make space for themselves. 2.23 At a broader level, for enabling a reasonable level playing field, there would have to be a gradual convergence in terms of the operating space and flexibility available to each segment. In terms of regulatory and prudential norms governing the banking operations, there is already a significant amount of convergence. In fact, this equitable application of regulatory policies across ownership groups has been one of the cornerstones of the regulatory regime. However, the same would have to be extended to managerial and operational flexibility based on good governance standards, specifically in case of PSBs.

Chapter 3 : Evolution of Bank Licensing Norms in India 3.1. Historically, till some banks were nationalised in 1969, commercial banks in India were privately held. The private sector banks played a crucial role in the growth of joint stock banking in India. At the time of independence in 1947, India had 97 scheduled private banks, 557 non-scheduled private banks and 395 cooperative banks. The commercial banks, many of which were controlled by business houses at that time, lagged in attaining the social objectives. Therefore, the Government of India nationalised 14 major commercial banks in 1969 and 6 more commercial banks in 1980. Thus about 91 per cent of the banking business in India was brought under PSBs. Since first phase of nationalisation, during next two decades, no banking licence was granted in private sector except Bharat Overseas Bank Ltd. 3.2. However, with the onset of economic reforms in the early nineties, the role of private banks has increasingly been recognised. From 1993 to end of September 2020, eight licensing guidelines have been issued by the Reserve Bank, of which four are for universal banks and four pertain to Differentiated Banks. The Reserve Bank has generally adopted consultative approach in framing these licensing guidelines. During this journey spanning almost three decades, certain specific guidelines/instructions/Master Directions and Discussion Papers have also been issued. A. 1993 Licensing Guidelines for new Private Sector Bank 3.3. The Committee on Financial Sector Reforms under Shri M. Narasimham, set up in 1991 for financial sector reforms, inter alia advocated opening up of the banking sector to the private entrepreneurs to bring in competition and efficiency in the banking industry, and made unequivocal recommendation to allow more private and foreign banks into the banking industry. It paved the way for licensing of new commercial banks in the private sector. Accordingly, in 1993, with increasing recognition of the need for competition, growing process of globalisation and adoption of more liberal policies, the Reserve Bank issued ‘Guidelines on Entry of New private sector banks-1993’. 3.4. Major provisions: Initial minimum required paid-up capital for such banks was set at ₹100 crore. The promoters' contribution for such a bank was to be determined by the Reserve Bank. Though it was stated that the shares of the bank should be listed on stock exchanges, no specific time line was prescribed. There was no explicit ban on setting up banks by large commercial/industrial houses. However, it was to be ensured at the time of licensing that they avoid the shortcomings, such as, unfair pre-emption and concentration of credit, monopolisation of economic power, cross holdings with industrial groups, etc., which beset the private sector banks prior to nationalisation. 3.5 Out of ten licences granted under these Guidelines during 1993-1994, four were promoted by financial institutions, one each by conversion of co-operative bank and NBFC into commercial banks, three by individual banking professionals and one by an established media house. Out of the three banks promoted by individual banking professionals, none has survived; while one has been compulsorily merged with a nationalised bank, the other two have voluntarily amalgamated with other private sector banks. Out of the remaining seven banks, one bank promoted by a media group has voluntarily amalgamated itself with another private sector bank. Thus, out of 10 banks licenced, only six are in existence at present. B. 2001- Licensing Guidelines for new banks in Private Sector 3.6 The Committee on Banking Sector Reforms (Narasimham Committee II), in 1998 recommended that the policy of licensing new private banks [other than local area banks (LABs)] may continue. The Committee also recommended that there should be well defined criteria and a transparent mechanism for deciding the ability of promoters to professionally manage the banks and no category should be excluded on a priori grounds. 3.7 After a review of the experience gained on the functioning of the new banks in the private sector, in consultation with the Government, the Reserve Bank issued revised licensing guidelines in 2001. 3.8 Major provisions: The initial minimum paid-up capital was raised from ₹100 crore to ₹200 crore, which was required to be raised further to ₹300 crore within three years of commencement of business. The promoters’ contribution was required to be a minimum of 40 per cent of the paid-up capital of the bank and it was to be locked in for a period of five years from the date of licensing of the bank. Promoters’ contribution in excess of the 40 per cent, was required to be diluted after one year of the bank’s operations. These banks were not allowed to be promoted by a large corporate/industrial house. However, individual companies, directly or indirectly connected with large corporate/industrial houses were permitted to participate in the equity of these banks up to a maximum of 10 per cent but were not allowed to have controlling interest in the bank. Conversion of an NBFC into private sector bank was permitted if it had impeccable track record. However, the NBFCs promoted by a large corporate/industrial house or owned/controlled by public authorities, including Local, State or Central Governments, were not eligible. The promoters, their group companies and the proposed bank were to accept the system of consolidated supervision by the Reserve Bank. These banks were not to be allowed to set up a subsidiary or mutual fund for at least three years from the date of commencement of business. In June 2002, the maximum limit of shareholding of Indian promoters in these banks was raised to 49 per cent of their paid up capital. 3.9 Two banks licenced under these guidelines were set up by individual banking professionals. C. 2004 - Guidelines for acknowledgement of transfer/allotment of shares in private sector banks 3.10 With a view to streamline the procedure for obtaining acknowledgement and removing uncertainties for investors including foreign investors [Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Financial Institutional Investment (FII) and Non-resident Indian (NRI)] in regard to the allotment or transfer of shares and indicate in a transparent manner the broad criteria followed by Reserve Bank for the purpose, in February 2004, Reserve Bank issued detailed guidelines. Private sector banks were advised to ensure through an amendment to the Articles of Association (AoA) that no transfer takes place of any acquisition of shares to a level of 5 per cent or more of the total paid-up capital of the bank unless there is a prior acknowledgement by the Reserve Bank. 3.11 To ensure that ownership and control of private sector banks remains in the hands of fit and proper persons, these guidelines also prescribed illustrative criteria for acknowledgement which inter alia included integrity, reputation and track record of applicant. Where acquisition or investment were to take the shareholding of the applicant to a level of 10 per cent or more and up to 30 per cent, the Reserve Bank prescribed certain additional stringent criteria. 3.12 Acknowledgement for transfer of acquisition or investment exceeding the level of 30 per cent were to be considered subject to meeting all the prescribed criteria and only in certain specified situations such as in public interest, desirability of diversified ownership of banks, soundness and feasibility of the plans of the applicant for the future conduct and development of the business of the bank; and shareholder agreements and their impact on control and management of the bank. D. 2005 - Guidelines on Ownership and Governance in private sector banks 3.13 In February 2005 the Reserve Bank issued detailed guidelines on ownership and governance of private sector banks. The broad principles underlying the framework of this policy was to ensure that the ultimate ownership and control of private sector banks is well diversified. While diversified ownership minimises the risk of misuse or imprudent use of leveraged funds, the fit and proper criteria, were viewed as over-riding consideration in the path of ensuring adequate investments, appropriate restructuring and consolidation in the banking sector. 3.14 Some of the major areas these guidelines covered included norms on shareholding in private sector banks, acquisition and acknowledgement related norms, dispensations permitting a higher level of shareholding in case of restructuring of problem/weak banks or in the interest of consolidation in the banking sector. These guidelines also prescribed that where ownership is that of a corporate entity, it is to be ensured that no single individual/entity has ownership and control in excess of 10 per cent of that entity. Large corporate/industrial houses were allowed to acquire, by way of strategic investment, upto 10 per cent holding subject to the prior approval of the Reserve Bank. Shareholder with other commercial affiliations were also placed under same restriction. 3.15 These guidelines prescribed that the aggregate foreign investment in private banks from all sources (FDI/FII/NRI) could not exceed 74 per cent. If any FDI/FII/NRI shareholding reaches and exceeds 5 per cent, either individually or as a group, it will have to comply with the criteria indicated in the ‘2004- Guidelines for acknowledgement’. Arrangements for continuous monitoring were also introduced in these guidelines putting the onus on the banks to ensure continuing compliance of the ‘fit and proper’ criteria and provide an annual certificate to the Reserve Bank. 3.16 All the instructions relating to acquisition of shares in private sector banks and shareholding/voting rights limits in private sector banks, were later consolidated in the form of Master Directions, issued in 2015 and 2016 respectively. E. Discussion Paper on Entry of New Banks in the Private Sector (2010) & the Guidelines for Licensing of New Banks in the Private Sector (2013) 3.17 In August 2010 the Reserve Bank released a Discussion Paper on “Entry of New Banks in the Private Sector” to seek views/comments of various stakeholders on following aspects delineated in the Discussion Paper: -

Minimum capital requirements for new banks and promoters’ contribution -

Minimum and maximum caps on promoters’ shareholding and other shareholders -

Foreign shareholding in the new banks -

Whether industrial and business houses could be allowed to promote banks -

Should NBFCs be allowed conversion into banks or to promote a bank -

Business model for the new banks. 3.18 Taking into account the feedback received on the Discussion Paper the draft guidelines on ‘Licensing of New Banks in the Private Sector’ were framed. The draft guidelines were placed on the website of the Reserve Bank in August 2011 for comments. The final guidelines for “Licensing of New Banks in the Private Sector” were issued in February 2013. 3.19 Major provisions: These banks were to be mandatorily set up through a wholly-owned Non-Operative Financial Holding Company (NOFHC). There was no bar on large corporate/industrial houses to be promoters. Individuals were not allowed to promote a bank. The NOFHC was to initially hold a minimum of 40 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank which would remain locked in for a period of 5 years from the date of commencement of business. Shareholding by NOFHC in excess of 40 per cent was to be brought down to 40 per cent of paid-up voting equity share capital within 3 years from the commencement of operations. Further, it has to be brought down to 20 per cent in 10 years and to 15 per cent within 12 years. Shares were required to be listed within 3 years from the date of commencement of business. The aggregate non-resident shareholding could not exceed 49 per cent for first 5 years from commencement of operations. No non-resident shareholder could acquire more than 5 per cent in the bank for first 5 years from commencement of operations. After 5 years extant FDI policy would be applicable. Initial minimum paid-up voting equity capital/net worth for converting NBFC was raised to ₹500 crore. Bank was required to maintain 13 per cent CRAR for first 3 years from commencement of operations. No entity other than the NOFHC can have shareholding or control in excess of 10 per cent of the paid-up voting equity capital of the bank. 3.20 Two banks were set up under these guidelines. F. Discussion Paper (2013) and the Guidelines issued thereafter for Small Finance Banks (2014) and Payments Banks (2014) 3.21 Immediately thereafter, the Reserve Bank released another comprehensive Discussion Paper in 2013, identifying certain building blocks for the reorientation of the banking structure with a view to addressing various issues such as enhancing competition, financing higher growth, providing specialised services and furthering financial inclusion. The overall thrust of the reorientation was to impart dynamism and flexibility to the evolving banking structure, while ensuring that the structure remains resilient and promotes financial stability. These discussions shaped contours of licensing policies and guidelines framed thereafter, and continue to do so even now. Small Finance Banks 3.22 Considering that small local banks can play an important role in the supply of credit to micro and small enterprises, agriculture and banking services in unbanked and under-banked regions in the country, the Reserve Bank decided to allow new “small banks” in the private sector. The final licensing guidelines were issued in November 2014. In terms of the activity scope, the SFBs are required to extend 75 per cent of Adjusted Net Bank Credit (ANBC) to the sectors eligible for classification as priority sector lending (PSL) by the Reserve Bank. At least 50 per cent of its loan portfolio should constitute loans and advances of upto ₹25 lakh. 3.23 Resident individuals/professionals with 10 years of experience in banking and finance; and companies and societies owned and controlled by residents were eligible to set up SFBs. Existing NBFCs, Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs), and LABs that were owned and controlled by residents could also opt for conversion into SFB. Large public sector entities and industrial and business houses, including NBFCs promoted by them were not eligible. The minimum paid-up equity capital for SFBs was kept at ₹100 crore. An NBFC/MFI/LAB converting into a SFB was required to have a minimum net worth of ₹100 crore. 3.24 The promoters’ minimum initial contribution to the paid-up equity capital of such bank shall at least be 40 per cent and gradually brought down to 30 per cent in 10 years and 26 per cent within 12 years from the date of commencement of business of the bank. If the existing NBFCs/MFIs/LABs converted into bank have diluted the promoters’ shareholding to below 40 per cent, but above 26 per cent, due to regulatory requirements or otherwise, then the minimum shareholding requirement is 26 per cent. Voluntary listing for SFBs with net worth less than ₹500 crore and mandatory listing for SFBs within 3 years of reaching net worth of ₹500 crore was prescribed. SFBs cannot establish subsidiaries to undertake para-banking activities. NOFHC structure is mandatory in case a promoter setting up an SFB also desires to start a Payments Bank. 3.25 If the SFB aspires to transit into a universal bank, such transition will not be automatic, but would be subject to fulfilling minimum paid-up capital / net worth requirement as applicable to universal banks; its satisfactory track record of performance as a SFB and the outcome of the Reserve Bank’s due diligence exercise. 3.26 Ten SFBs were licenced under these guidelines. Payments Banks (PBs) 3.27 The licensing guidelines for PBs were issued in November 2014. The objective of setting up of PBs was to further financial inclusion by providing small savings accounts and payments/remittance services to migrant labour workforce, low income households, small businesses, other unorganised sector entities and other users. 3.28 Scope of their activities includes acceptance of demand deposits (initially restricted to holding a maximum balance of ₹1 lakh per individual customer); issuance of ATM/debit cards (cannot issue credit cards); payments and remittance services through various channels; distribution of non-risk sharing simple financial products like mutual fund units and insurance products, etc. The PBs can not undertake lending activities. 3.29 Eligible promoters included existing non-bank Pre-paid Payment Instrument (PPI) issuers; individuals/professionals; NBFCs, corporate Business Correspondents (BCs), mobile telephone companies, super-market chains, companies, real sector cooperatives that are owned and controlled by residents; and public sector entities. A promoter/promoter group could have a joint venture with an existing scheduled commercial bank to set up a PB. Promoter/promoter groups had to be ‘fit and proper’ with a sound track record of professional experience or running their businesses for at least a period of five years in order to be eligible to promote PBs. The minimum paid-up equity capital for PBs was fixed at ₹100 crore. The promoters’ minimum initial contribution to the paid-up equity capital of such PBs shall at least be 40 per cent, which is to be kept locked in for the first five years from the commencement of its business. No dilution schedule was prescribed. Voluntary listing with net worth less than ₹500 crore and mandatory listing within 3 years of reaching net worth ₹500 crore was prescribed. These banks cannot establish subsidiaries to undertake para-banking activities. 3.30 The Reserve Bank had announced its decision to grant ‘in principle’ approvals to 11 entities to set up PBs. Subsequently, licences were issued to seven PBs and all the banks were set up. Later, in 2020 one bank has decided for voluntary winding up of its business, and surrendered its licence. G. 2016- Guidelines for ‘on tap’ Licensing of Universal Banks in the Private Sector 3.31 After a thorough examination of the pros and cons, the discussion paper on ‘Banking Structure in India – The Way Forward’, issued in 2013 made out a case for reviewing the current ‘Stop and Go’ licensing policy and for considering a ‘continuous authorisation’ policy on the grounds that such a policy would increase the level of competition and bring new ideas into the system. The feedback on the Discussion Paper broadly endorsed the proposal of continuous authorisation with adequate safeguards. Building on the Discussion Paper and after carefully examining the views/comments received on the draft guidelines from various stakeholders, as also, using the learning from the recent licensing process, such as, the experience of licensing two universal banks in 2014 and granting in-principle approvals for SFBs and PBs, the Reserve Bank worked out the framework for granting licences to universal banks on a continuous basis. These guidelines were issued on August 1, 2016. 3.32 Major provisions: Some of the key aspects of the Guidelines include: (i) resident individuals and professionals having 10 years of experience in banking and finance at a senior level are also eligible to promote universal banks; (ii) large corporate/industrial houses are excluded as eligible entities but are permitted to invest in the banks up to 10 per cent; (iii) NOFHC has been made non-mandatory in case of promoters being individuals or standalone promoting/converting entities who/which do not have other group entities; (iv) Not less than 51 per cent of the total paid-up equity capital of the NOFHC shall be owned by the promoter/promoter group, instead being wholly owned by the promoter group; and (v) Existing specialised activities have been permitted to be continued from a separate entity proposed to be held under the NOFHC subject to prior approval from the Reserve Bank and subject to it being ensured that similar activities are not conducted through the bank as well. 3.33 The listing time line was raised to 6 years from commencement of business by the bank as against earlier prescription of 3 years. The time for bringing down the shareholding in excess of 40 per cent by Promoters/NOFHC to 40 per cent was increased from 3 to 5 years. Further, longer time was given for dilution of shareholding i.e. 30 per cent in 10 years and to 15 per cent within 15 years. H. 2018- Voluntary Transition of Primary (Urban) Co-operative Banks (UCBs) into Small Finance Banks (SFBs) 3.34 Over the years, a few UCBs along with high rate of growth, have expanded their area of operation to multiple States thus acquiring the size and complexities of a small commercial bank. Discussion Paper on ‘Banking Structure in India - The Way Forward’ issued in 2013 envisaged conversion of UCBs into commercial banks and exploring the possibilities of converting some UCBs into commercial banks or small banks. The High Powered Committee (HPC) on UCBs recommended voluntary conversion of large Multi-State UCBs into Joint Stock Companies and other UCBs, which meet certain criteria, into SFBs. 3.35 In keeping with the fast paced changes in the banking space and in order to facilitate growth, a scheme for voluntary transition of UCBs into SFB is considered a step forward to provide full suite of products / services, sustain competition, raise capital, etc. Accordingly, this scheme was introduced for voluntary transition of eligible UCB into SFB by way of transfer of assets and liabilities. The detailed scheme was announced on September 27, 2018. 3.36 Major provisions of the scheme are as given below: -

Eligible applicants: UCBs with a minimum net worth of ₹50 crore and CRAR of 9 per cent and above. -

Promoters: A group of individuals/professionals, having an association with UCB as regular members for a period of not less than three years and approved by General Body with 2/3rd majority of members present and voting. The promoters must be residents and shall have ten years of experience in banking and finance. -

Capital requirement: Minimum net worth of ₹100 crore from the date of commencement of business and the Promoters shall maintain at least 26 per cent of the paid-up equity capital. -

The eligible UCBs can apply for conversion to SFBs under 2019 ‘on tap’ SFB licensing guidelines. I. 2019 - “Guidelines for ‘on tap’ Licensing of Small Finance Banks in the Private Sector” 3.37 It was mentioned in the licensing guidelines for SFBs issued in 2014 that after gaining experience in dealing with these banks, the Reserve Bank would consider receiving applications on a continuous basis. Accordingly, the draft guidelines were published on the website of the Reserve Bank on September 13, 2019 inviting comments from the stakeholders and members of the public. Taking into consideration the responses received, the final guidelines were issued on December 5, 2019. 3.38 Major changes in these Guidelines, when compared with earlier Guidelines on SFBs dated November 27, 2014, are: (i) The licensing window will be open on-tap; (ii) minimum paid-up voting equity capital / net worth requirement shall be ₹200 crore; (iii) for UCBs, desirous of voluntarily transiting into SFBs initial requirement of net worth shall be at ₹100 crore, which will have to be increased to ₹200 crore within five years from the date of commencement of business. Incidentally, the net-worth of all SFBs currently in operation is in excess of ₹200 crore; (iv) SFBs will be given scheduled bank status immediately upon commencement of operations; (v) SFBs will have general permission to open banking outlets from the date of commencement of operations; (vi) PBs can apply for conversion into SFB after five years of operations, if they are otherwise eligible as per these guidelines. 3.39 As may be seen with above, guidelines for licensing of banks have kept pace with changing ecosystem; various developments in the area of technology, economy, capital markets; legislative reforms and developments; increasing needs of customers (particularly marginalised section of the society); need to extend reach of banks upto last mile; international practices; improving governance standards; etc. A comparative position of all major licensing guidelines for private sector banks is furnished in Annex II. Summary of all licensing guidelines is furnished in Annex III.

Chapter 4 : International Experience 4.1 Internationally, most banking jurisdictions require banks to be widely held to avoid concentration of control in the interest of governance and financial stability. A survey of the regulatory regimes in major countries brings out that most of the regimes address the concerns relating to bank ownership through a set of restrictions on the ownership of bank stock on the following parameters: (a) level of ownership by single person/related entities (b) requirements on ultimate beneficial ownership and control (c) ownership restrictions for domestic entities based on nature of entity • non-bank financial entities • non-financial entities • other banks (d) ownership restrictions for foreign entities 4.2 A comparative position of international practices and regulatory guidelines in respect of bank ownership in some advanced jurisdictions vis-à-vis India, is furnished in Annex IV. The major inferences that may be drawn from these practices/statutory provisions prevalent in other jurisdictions are enumerated below. (i) Most of these countries do not have an explicit cap on the maximum shareholding by a single person/entity. Australia seems to be an exception among the major developed countries, with prohibition on acquiring voting rights of more than 20 per cent. In this regard, Canada has a unique regime which requires banks with equity greater than $ 12 billion to be widely held, with no one entity in control; in banks with equity $2 - $12 billion a person is permitted to have aggregate shareholding upto 65 per cent with at least 35 per cent being publicly held; and no restrictions for smaller banks. (ii) Ownership concentration is regulated through a layered threshold structure as per which any person wishing to acquire/increase shareholding in a bank beyond those thresholds would be required to seek regulatory approval for the same. The qualifying threshold level is mostly 10 per cent with subsequent triggers at 20 per cent, 30 per cent and 50 per cent (Malaysia and Singapore have 5 per cent, apart from India). Many of these jurisdictions also have reporting requirements within specified timeframes upto certain thresholds by the acquirer as well as the bank particularly for listed banks. (iii) While there is a concept of ‘promoter’ in India with separate limits prescribed for shareholding, the same is not found in other jurisdictions. Persons are classified as major shareholders (e.g. Canada), controllers (e.g. Singapore), principal shareholder (e.g. USA) depending on their shareholding, voting rights, etc. (iv) The basis for the thresholds include an ability of the person to exercise control directly or indirectly by virtue of having ‘significant interest’ (e.g. Canada) or ‘significant influence’ (e.g. New Zealand, UK, Sweden) or ‘relevant interest’ (e.g. Australia), ‘material influence’ (e.g. Japan) through shareholding, voting rights, power to issue directions etc. (v) The above structure applies to direct as well as indirect control by a person singly or jointly through a group of associates or related parties. (vi) The regulators give approvals on a case to case basis subject to a number of considerations including the overall sectoral impact of the transaction and the satisfaction of ‘fit and proper’ principles by the person/s acquiring the stake, which may inter alia include reputation, financial soundness, credit standing etc. In case of acquirers being non-individuals, the due diligence may extend even to the parent institution or major shareholders. (vii) Acquirers of shares beyond thresholds need to provide comprehensive information to the authorities for their approval including the intent of purchase, terms and conditions, if any, manner of acquisition, source of funds, etc. (viii) In terms of the nature of the entity, non-banking financial firms and non-financial firms are permitted to acquire shares in banks subject to the overall ceilings in respect of single entity in most countries albeit with regulatory approval. (ix) In most of the countries, the FDI entry is subject to fulfilment of set of entry norms and licences are accorded on a case to case basis within the overall policy framework. Foreign portfolio investment, on the other hand, is treated similar to domestic portfolio investment and is subject to the guidelines in place in respect of shareholding by a single person/entity on a non-discriminative basis. 4.3 As regards ownership of banks by non-financial firms, including corporate/industrial houses, most countries do not have an explicit restriction, except a few as discussed below. However, the entry is restricted through an authorisation framework. Even in some of these countries where there is no explicit restriction, the actual ownership of the banking system by such non-financial firms is not too high.4 4.4 Some of the key jurisdictions which have explicit limits on shareholding by non-financial firms include, apart from India, the United States, Australia, South Korea, Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia. In the United States, commercial enterprises are not allowed to own a bank due to the concept of separation of banking and commerce. Though the limitation in the 1933 Glass-Stegall Act (GSA), strictly separating banking from securities and insurance activities, has been rolled back to a large degree as a result of the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), the concept of the separation of banking and commerce still exists. This has been a contentious issue over the years and has been debated from time to time. 4.5 Many jurisdictions also have in place comprehensive frameworks for regulation of transactions within large conglomerates. In the US, sections 23A and 23B of the Federal Reserve Act specify the statutory restrictions on transactions between a member bank and its affiliates. In the European Union (EU), the Financial Conglomerates Directive provides a framework for supplementary layer of prudential supervision of financial conglomerates addressing the concerns behind such transactions.

Chapter 5 : Issues and Perspectives 5.1 Lock-in period for promoters’ initial shareholding, limits on shareholding in long run, dilution requirement and voting rights 5.1.1 As mentioned previously, banking regulation prefers wider shareholding in banks to concentrated shareholding. Towards this end, apart from prescribing timelines for mandatory listing of the shares of the banks, shareholding ceilings have been prescribed along with the dilution schedule for shareholding of promoters of the banks. 5.1.2 The limits on shareholding, lock-in requirements and dilution schedule for promoters prescribed in various guidelines issued by the Reserve Bank are summarised in the following table: | Licensing Guidelines→ | 2001 | 2013 | 2014

SFB | 2016

On-tap

Universal | 2019

On-tap SFB | | Min initial holding | 40% of paid up (voting) equity capital | | Lock in for this | 5 years | Dilution schedule for excess above minimum required capital (40%)

(from date of commencement of business) | After 1 year - 40%

(raised to 49 % in 2002)

(Bank to seek RBI approval if extra time required) | Within 3 years -

40% | Within 5 years-

40% | Within 5 years-

40% | Within 5 years-

40% | | | Within 10 years

20% | Within 10 years

30% | Within 10 years

30% | Within 10 years

30% | | | Within 12 years

15% | Within 12 years

26% | Within 15 years

15% | Within 15 years

15% | 5.1.3 As regards non-promoters, the extant Master Directions on Ownership in Private Sector Banks, 2016 provide for a three-tier long run shareholding limits for investors in a bank: Individuals and Non-financial institution/ entities – 10 per cent; Non-regulated or non-diversified and non-listed financial institutions – 15 per cent; and, Regulated, well diversified, and listed/ supranational institution/ public sector undertaking / Government financial institutions – 40 per cent. 5.1.4 The issue of subsequent changes in the shareholding of the promoting entity has also been recognised as an important consideration in the recent past. In respect of licences issued to PBs, SFBs, IDFC First Bank and Bandhan Bank, the Reserve Bank had mandated that any change of shareholding by way of fresh issue or transfer of shares to the extent of 5 per cent or more in their respective promoting entities also shall be with the prior approval of the Reserve Bank. This condition was not part of the respective licensing guidelines but was incorporated subsequently either in the ‘Terms and Conditions’ of the licence or the ‘in-principle approval’ or the banks were separately advised to amend their memorandum of association/article of association suitably. 5.1.5 Even though the instructions in this regard seems to have been fairly stabilised, the IWG felt that the following aspects may require additional examination: (i) The extant instructions require the promoters’ shareholding to be locked-in at not less than 40 per cent during the first five years of operations of a new bank. Post the lock-in period, the promoters’ shareholding should not be more than 40 per cent. Whether there is a need to review the lock-in period and also whether there should be a cap on initial holding, needs to be examined. (ii) While the voting rights cap has been raised from 15 per cent to 26 per cent of the total voting rights of all shareholders of the banking company through notification issued by the Reserve Bank in July 2016, the extant dilution schedule requires the promoters’ shareholding to be reduced to 15 per cent in the long run (i.e. in 12 or 15 years in 2013 and 2016 guidelines respectively). This necessitates review of the threshold on long term shareholdings. (iii) Not only the levels to which shareholding of promoters has to be brought down but also timelines to achieve the target is at variance in different guidelines. There is a need to harmonise them, including for the existing banks. (iv) The existing three-tier structure for long-term shareholding by non-promoters, particularly the provision to allow 40 per cent holding for well-diversified entities, is not in alignment with the norms relating to promoters and needs to be reviewed. (v) With regard to subsequent changes in shareholding at the promoter entity level, whether the requirement of prior approval of the Reserve Bank can be substituted with a reporting requirement. (i) Initial lock-in requirement 5.1.6 The extant instructions require that the promoters’ shareholding in the bank shall be at least 40 per cent in the initial five years of operations of a new bank. Since the licence is issued based on due diligence of the promoter group and satisfaction that the promoter group is indeed ‘fit and proper’ among other aspects, the stipulation of lock-in period seeks to lock in the credibility of the control of the promoter group till the business is properly established and stabilised. Further, higher holding in beginning with lock-in for five years also ensures that the promoters remain committed to the business in the formative years, providing necessary strategic direction. Majority of experts with whom the IWG interacted, were also of the view that a higher initial stake requirement makes sure that only serious and financially sound promoters come forward. Further, on the issue whether there should be upper limit/cap on the initial holding by a promoter, the IWG observed that the extant instructions do not mandate any limit in this regard and felt that status quo may continue. 5.1.7 In view of the above, the IWG recommends that no change may be required in the extant instructions related to initial lock-in requirements. Thus the 40 per cent limit would be the floor in terms of the initial holding by a promoter, with no upper ceiling, during first five years. (ii) Maximum permitted holding in long run (Final Dilution) 5.1.8 Another issue deliberated by the IWG was whether the extant ceiling on promoters’ shareholding at 15 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank needs a revision in view of revised ceiling for voting rights at 26 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank. Extant Reserve Bank Guidelines for ‘on tap’ Licensing of Universal Banks in the Private Sector; August 2016, inter alia, provide: a) Shareholding by the promoter/s and the promoter group / NOHFC in the bank in excess of 40 per cent of the total paid-up voting capital shall be brought down to 40 per cent within five years from the date of commencement of business of the bank b) The shareholding by promoter/s and promoter group / NOHFC in the bank shall be brought down to 30 per cent of the paid-up voting equity capital of the bank within a period of 10 years, and to 15 per cent of the paid-up voting equity capital of the bank within a period of 15 years from the date of commencement of business of the bank 5.1.9 During the interaction with some banks and experts it was opined that this trajectory of compulsory dilution by the promoters needs a review. The experts whom the IWG engaged with were broadly of the view that while in principle the requirement of higher shareholding in the initial years with subsequent dilution makes sense, the long-run threshold needs to be higher at 26 per cent. The group deliberated on the international practices and also the views of the experts in this regard. International practices -

In some of the jurisdictions in Asia, like Indonesia, it was observed that a 25 per cent stake is defined as a controlling stake, requiring central bank approval. Non-controlling stakes, lower than 25 per cent, face no other constraints and are permitted without approval. This freedom is permitted for overseas investors as well. -

In Japan, the threshold is defined as applicable to a major shareholder, and is pegged at 20 per cent (15 per cent if the shareholder has material influence). Major shareholders need central bank approval, while others do not. Thus the threshold is 15 per cent if control is sought to be exercised, and 20 per cent in other situations as for instance in a purely financial investment. -

In South Korea, the norms are more nuanced, and differentiate between a non-financial business (termed NBFOs) and a financial business. NBFOs can own upto 4 per cent freely, and can go upto 9 per cent with central bank approval. Financial businesses can own upto 10 per cent freely, but can also go higher with successive approvals to get beyond 10, 25 and 33 per cent. -

In Germany, there appears to be no specific regulations limiting controlling or major shareholding in banks. Views of experts -

Excessive focus on limits on economic ownership seems contrary to legislative intent. -

Voting control achieves the policy parameters of diversified ownership. -

Most other jurisdictions do not enforce similar limits on bank ownership, though there are due diligence thresholds. 5.1.10 In case the Reserve Bank finds any major shareholder (including promoter) not meeting ‘fit and proper’ criteria, at any point of time, it is statutorily empowered to restrict his voting rights to 5 per cent of the paid-up voting equity capital of the bank [under Section 12B(8)], which can be a strong check. 5.1.11 The IWG also noted that it will result in harmony in various guidelines (2014 SFB guidelines allow 26 per cent holding in long run, allows NBFCs/LABs to start with 26 per cent if the entity has already diluted holding due to regulatory requirements). Permitting higher shareholding up to 26 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank will enable promoters to infuse higher funds which are critical for expansion of banks and work as a cushion to rescue the bank in times of distress/cyclical downturn. 5.1.12 Taking into account the feedback of experts and also looking at the international practices in this regard, the IWG felt that if India's private sector banks are to grow, it appears desirable that they be permitted to access the pool of capital available in India and elsewhere without imposing excessively narrow investment limits. While it is desirable to have widely held banks to ensure that there is no controlling stake vested in one person/entity but at the same time when individual holdings are small and shareholders are diffused, they also tend to be disengaged. 5.1.13 It was also observed that the P. J. Nayak Committee (constituted by Reserve Bank), in 2014, had recommended promoters’ holding of 25 per cent recognizing that low promoters’ shareholding could make banks vulnerable by weakening the alignment between management and shareholders. 5.1.14 On balance therefore, the IWG recommends that the cap on promoters’ stake in the long run (i.e. 15 years) may be raised from the current levels of 15 per cent to 26 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank. This will balance the need for diversified ownership on the one hand and bring more skin in the game for the promoter, on the other. The 26 per cent stake would serve as the threshold for maximum holding by a promoter in long run. This stipulation would mean that promoters, who have already diluted their holdings to below 26 per cent, will be permitted to raise it to 26 per cent, subject to meeting ‘fit and proper’ status. The promoter, if he/she so desires, can choose to bring down holding to even below 26 per cent, any time after the lock-in period of five years. 5.1.15 As regards the long term shareholding specified for promoters being “Regulated, well diversified, and listed/ supranational institution/ public sector undertaking / Government financial institutions”, the IWG was of the view that in-principle there should not be any distinction in the threshold for long-term shareholding based on the nature of the promoter entity. Further, such generic qualifiers as ‘regulated, well diversified’ may dilute the rigour of the process. The IWG therefore recommends that to keep regulations simple but meaningful, a uniform shareholding limit at 26 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank for all promoter categories may be stipulated. (iii) Sub-targets for dilution 5.1.16 Between 5-15 years, the extant guidelines provide for an intermediate threshold of 10 years, by when the shareholding has to be brought down to 30 per cent (20 per cent for banks licensed under 2013 guidelines). The IWG deliberated on the need for continuing with these intermediate thresholds and concluded that the same may not be necessary. Once the Reserve Bank has prescribed the initial lock-in requirement for 5 years and the long-term dilution schedule of 15 years, it should be left to the bank to plan out the exact path depending on economic environment and market situations. The IWG therefore recommends that the intermediate sub-targets may be dispensed with. Instead, at the time of issue of licences, the promoters may submit a dilution schedule which may be examined and approved by the Reserve Bank. The progress in achieving these agreed milestones must be periodically reported by the banks and shall be monitored by the Reserve Bank. (iv) Shareholding by non-promoters 5.1.17 As regards non-promoters, the extant instructions provide for a three-tier long run shareholding limits for investors in a bank: Individuals and Non-financial institution/ entities – 10 per cent; Non-regulated or non-diversified and non-listed financial institutions – 15 per cent; Regulated, well diversified, and listed/ supranational institution/ public sector undertaking / Government financial institutions – 40 per cent. The IWG deliberated on the imperative for this three-tier stipulation and the rationale for different thresholds based on the nature of the non-promoting entity. -

The IWG was of the view that the arguments applicable for restricting the level of shareholding by promoters in the long run, equally apply to any major shareholder in the bank as well. The concerns relating to influence over the affairs of the bank by any major shareholder, not just the promoter, need to be addressed. Therefore, there is little rationale for continuing with a higher threshold beyond 26 per cent for any shareholder. -

Further, as regards the 10 per cent limit for individuals and non-financial institutions, the IWG felt that in view of the requirement of mandatory prior clearance by the Reserve Bank for exceeding the shareholding beyond 5 per cent, in line with international norms, there may be case for increasing this threshold a notch higher upto 15 percent. The raise will also be in sync with the raise recommended for promoters’ holdings. However, the due diligence process as prescribed in the Master Directions on Prior Approval, 2015, for shareholding above 10 per cent may be continued for such holding. 5.1.18 Taking into account the above, the IWG recommends that the current long-run shareholding guidelines for non-promoters may be replaced by a simple cap of 15 per cent of the paid-up voting equity share capital of the bank, for all types of non-promoter shareholders in the long run. However, the Reserve Bank should reserve the right to prescribe any lower ceiling on holding or curb voting rights of the promoters/non-promoters, if at any point of time they are found to be not meeting ‘fit and proper’ criteria. 5.1.19 It was also observed by the IWG that while non-promoter investors may act in concert to have control over the affairs of the bank, they may keep individual person’s shareholding below 5 per cent to circumvent the requirement of ‘fit and proper’ test by the Reserve Bank. There is a need to have close monitoring on such efforts by banks as well as by the Reserve Bank and deterrent regulatory/supervisory actions, as may be warranted, including cancellation of bank’s licence. 5.1.20 Further, the IWG is also of the view that the provisions to permit any higher holding by a promoter/investor in special circumstances as mentioned in paragraph 5 (iv) of MD on Ownership [such as relinquishment by existing promoters, rehabilitation / restructuring of problem / weak banks / entrenchment of existing promoters or in the interest of the bank or in the interest of consolidation in the banking sector, etc.] may be continued. 5.1.21 A comparative position of various type of limits on holdings, existing as well as recommended by the IWG are furnished in the following table. | Table: Limits on shareholding in long run (15 years), in percentage: | | Category | Existing | Recommended