| Preface Digital payments are a gateway for financial and digital financial inclusion of the poor and marginalised communities, particularly in the remote and underdeveloped regions of India. As part of the Programme Funding Scheme of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the Centre for Rural Management (CRM) conducted a field study in the ten inhabited islands in the Union Territory (UT) of Lakshadweep to analyse the present status of digital financial literacy and inclusion in the islands. While there have been studies to assess and evaluate the growth of digital financial literacy and inclusion in India, only limited research is available for UTs, particularly for the Lakshadweep Islands on the penetration of digital financial literacy and the popularity of digital payments. This study titled Status of Digital Financial Literacy in Lakshadweep Islands: Bottlenecks and Way Forward attempts to address these gaps. Acknowledgements We express our sincere gratitude to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for entrusting us with this project and giving us this opportunity. We are grateful to the RBI team for their valuable feedback and suggestions during each stage of the study including the report preparation. Thanks are due to the Department of Economic and Policy Research of RBI led by Smt. Rekha Misra for the financial support for this project. We are grateful to Dr. Pallavi Chavan and Dr. Priyanka Upreti from the Development Research Group of RBI for constant support and guidance in preparing the study report. We also acknowledge the support from Ms. Sona Chinngaihlian, Ms. Parul Singh along with other RBI officials namely, Ms. Tamanna Mooshahary, Mr. Abhishek Kumar, Mr. Nagarjun G, Mr. Ankur Jarora and Mr. Kamrul Islam for their useful comments and suggestions. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the people of Lakshadweep and the UT administration for their cooperation and assistance to our team during the research and field study in the islands. We are deeply grateful to the Advisor to the Administrator of the UT of Lakshadweep, District Collector and Directorate of Planning, Statistics and Taxation, Lakshadweep Administration. We express our sincere thanks to the President cum chief counsellor, Vice-president cum counsellor of the district panchayat, elected members and Chairpersons of village (dweep) panchayats in all the islands. We also convey our heartfelt gratitude to the respondents of the ten islands. This includes the business community, bank officials, school authorities, Self-Help Groups (SHGs), cooperative societies and civil society organisations. We acknowledge and extend our warmest thanks to Prof. K. J. Kurian, Prof. John S Moolakkattu, Shri E. P. Attakoya Thangal, Prof. Jose Sebastian, Shri Misbah Ashiyoda, Prof. P.P. Pillai, Prof. T.M. Joseph, Dr. Muneer Babu, Shri Ali Manikfan, Prof. K Gireesan, Shri B. R. Babu, all other faculty members and consultants of CRM for their inputs, suggestions and guidance. This research study would not have been successful without our team's dedication, co-operation and full-fledged support, particularly Shri C.V. Balamurali, Shri T.V. Thilakan, Ms. Rekha V, Ms. Shamla Beevi, Ms. Siji K.V, Ms. Manasi Joseph, Ms. Safira T K, Ms. Shajna Beegum B, Ms. Siyana B.N, Ms. Jubariyath A, Shri Shahul Hameed, Ms. Beebi Sumayya, Ms. Abidha Ahamed, Ms. Rahana Ziya, Ms. Hafeeza Beegum, Ms. Amina Beevi, Ms. Ayishummabi, Ms. Shamshad Begum, Ms. Akeela, Ms. Hajrabi T, Ms. Sarjeela K.P, Ms. Nilofar Eduibrahimgothi, Ms. Afeefa, Ms. Afeela, Ms. Akeela, Ms. Siffana and Ms. Abida M. We are also thankful to Shri M Yousuf (Late), Shri Ahmed Haji Achada, Shri B Hassan, Shri L G Ibrahim, Shri U C K Thangal, Ms. Noorjahan K K, Shri K R B Ismail and Shri Ibrahim Manikfan Oludu for providing historical insights on the study area. We record our heartfelt gratitude to all those who helped in this professional and academic venture. We hope the findings and observations from this study will become instrumental in policy formulation and implementation in making digitally inclusive India a reality. Dr. Jos Chathukulam

Director

Centre for Rural Management (CRM), Kerala Executive Summary The Centre for Rural Management (CRM) conducted a field study during July-September 2022 in all the ten inhabited islands in Lakshadweep - Agatti, Amini, Andrott, Bitra, Chetlat, Kadmat, Kalpeni, Kavaratti, Kiltan and Minicoy - to analyse the present status of digital financial literacy and digital financial inclusion. This project was undertaken as part of the Programme Funding Scheme of the Reserve Bank of India. The household was taken as the unit of the study and a total of 1,024 households (with a total of 4,598 members) were interviewed in all the inhabited islands to assess their digital financial literacy, familiarity with digital financial transactions and expertise in using it. Apart from individual households, SHG members, bank employees, school authorities, students and business-persons in the islands were also interviewed. Stratified random sampling based on income, gender, and landholdings was adopted in the study. The sample size of each island was taken proportionate to the population of the respective islands. To collect the relevant data and information from the sampled population, following five self-administered questionnaires were used: (1) Household level questionnaire for assessing the level of digital and financial inclusion among the selected households of Lakshadweep Islands for men, women and students separately; (2) Questionnaire for educational institutions; (3) Questionnaire for banks; (4) Questionnaire for SHGs; and (5) Questionnaire for business groups. The data collected from the islands revealed that all respondents had bank accounts owned either jointly or individually1. In comparison, 76 per cent and 78 per cent of adults worldwide and in India, respectively, have been reported to have a bank account as per World Bank’s Global Findex database of 2021. Most respondents used their savings bank accounts due to the trust that their money will be safe. More than 90 per cent of the respondents used their bank accounts for savings. About 80 per cent of the respondents operated their accounts independently while the remaining with assistance from others. There was a considerable difference between men and women regarding banking habits, including the decision to operate their accounts on their own even though there was no gender gap in ownership of accounts. While 91 per cent of the men operated their accounts by themselves, the corresponding figure among women was 71 per cent. This was mainly due to time and travel constraints for women. While Lakshadweep is a matrilineal society, the role of women and their lived experiences are shaped by patriarchal influences2. The spread of education among women has, of course, helped to reduce the impact of such influences. The gender gap was visible even in various modes of operating the bank account. While 68 per cent of respondents visited the bank, men visited banks more than women. During the field visit, it was also observed that women involved in household chores like cooking, washing, and child care hardly got time to visit the bank. In comparison, working women had the convenience, time, and freedom to visit the bank. The dependence on Bank Mitra was found relatively less among the islanders as less than one per cent sought their assistance. The only exception was Bitra island, where people depended on a Bank Mitra for their banking needs as there was no bank operating on this island. During the field visit, it was observed that the respondents were reluctant to take up the job of Bank Mitra; lack of fixed monthly wages and social security were cited by them as the reasons for their reluctance. Along with the high level of financial inclusion, digital literacy was also found high among the respondents in the islands. Various studies, including the latest National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) has also ascertained the same. The level of basic digital literacy was assessed in terms of possession as well as competency to use mobile phones and computers. The majority of men and women in the islands had a mobile phone. The research team observed at least three smartphone users each in every selected household in the islands. More than 70 per cent of the respondents reported have used Internet and computers at some point in their lives. The Department of Education had conducted digital literacy courses in the schools and most of them had functional computers3 that were mainly used for administrative and pedagogical purposes. Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) are one of India's earliest and most popular forms of digital banking using debit/credit cards. About 90 per cent of the respondents in the islands had ATM cards, with 95 per cent coverage for men and 85 per cent for women. About 80 per cent of the respondents in the islands used ATM cards; the percentage of usage was 91 per cent for men and 72 per cent for women. Women often gave their cards to family members to operate. Some women admitted that although they knew how to operate the cards, they were hesitant to use them alone. Incidents like cards and cash getting stuck had often caused fear and panic for them. Men’s familiarity with digital financial modes stemmed from their proficiency with and exposure to digital technology. Men often went to the mainland for work and educational purposes than women leading to greater exposure to digital technologies and platforms for them. Not surprisingly therefore, gender was a key determinant of digital financial literacy and digital financial inclusion in the islands. Among the surveyed 10 islands, in Bitra, respondents largely depended on ATM as there was no bank branch. Though these residents had bank accounts in Chetlat island, the travel time prevented them from visiting the branch. However, given the pressure on the ATM in Bitra, it often ran out of cash and faced frequent breakdowns. Internet banking4 had only few takers, while more than one-third of the respondents were into mobile banking5 in the islands. The discomfort and insecurity due to poor Internet connectivity was the major factor preventing people from using Internet banking. The users were also wary of the technical glitches and transaction failures. Lack of “perceived need” was another major reason that prevented people from using Internet banking. Needless to say, the gender gap in the usage of digital payments was relatively high. Though demographic factors like age, gender and income are crucial in enabling a person’s usage of digital payment methods, the trends emerging from the islands suggested that Internet/network connectivity heavily influenced the perception, decision to adopt and trust in digital payment methods. As regards digital hygiene, only 30 per cent of the respondents6 were aware of it. However, most of the inhabitants who were familiar with digital financial transactions, had adopted digital hygiene practices. There was basic financial inclusion among the students in the islands, with all of them having bank accounts. Interestingly, the digital financial inclusion was quite limited with only a small number of students (in the age group of 18 to 25) using ATM cards. None of the SHGs in the islands used ATMs, Internet and mobile banking. This could be because SHGs are only allowed to operate joint bank accounts. In comparison, there was reasonable financial inclusion and digital financial inclusion among the business groups7. The schools in the islands mostly had joint bank accounts and hence they could not avail the ATM card facilities. As regards credit, most respondents relied on banks. There was limited reliance on cooperatives, Micro Financial Institutions (MFI) and Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs). One of the possible reasons for this was also because a few NBFCs operated in the islands. The respondents also found interest rates offered by the banks to be more transparent and affordable. As regards consumer protection, fewer respondents were aware of the Banking Ombudsman scheme. The islanders and bank employees were aware of the illegal digital loan lending apps. Lakshadweep is a society with robust social capital including trust, reciprocity and networking; and despite being secluded from the mainland, the people on the islands exhibited trust in banks. The respondents in Bitra, despite not having a bank, had opened accounts in the adjacent island and sought the assistance of a Bank Mitra or ATMs for their financial transactions. On the whole, despite the limited real economic activity on the islands in the form of fisheries and tourism, the financial sector on the islands was well-entrenched primarily owing to banks. Strengthening the mobile network connectivity and ensuring high-speed Internet connectivity were key to expanding digital financial inclusion on the islands. The SHGs in Lakshadweep, popularly known as Dweepshrees (inspired by Kerala’s Kudumbashree) can also be used to transform Lakshadweep into a digitally inclusive society, particularly for women. The “Bank Sakhi” (Women Banker Friend) concept can be introduced in Lakshadweep and members of SHGs can be actively recruited as Bank Sakhis. Establishing banks in remote areas and ensuring their smooth operation for enhancing inclusion is a challenge, not just in India but globally. However, Lakshadweep sets a good example in this regard, particularly in terms of inculcating savings and payment habits among the inhabitants, although the geography of these islands and the high levels of literacy may make them a unique case for study. Banks are an integral and trusted part of the lives of people on the islands and have fostered economic prudence. Going forward, the financial inclusion experiment can be broadened to increase the access to bank credit in these islands. Chapter 1 - About the Study This chapter offers a brief profile of Lakshadweep while explaining the motivation, and objectives of this study. Lakshadweep, the smallest Union Territory (UT) of India, is an archipelago of 36 islands. It is a uni-district UT with a total surface area of around 32 sq. km. The administrative headquarters is in Kavaratti. It became a UT in 1956 and was given its present name in 1973. The UTs in India, without legislatures, are governed by an Administrator appointed by the President of India and the same applies to the islands as well. Located about 400 km west of Malabar Coast, the Lakshadweep UT comprises 36 islands, out of which ten are inhabited and 17 uninhabited islands attached to islets, four newly formed islets, and five submerged reefs. The inhabited islands are Agatti, Amini, Andrott, Bitra, Chetlat, Kadmat, Kalpeni, Kavaratti, Kiltan, and Minicoy. As per the Census 2011, Lakshadweep is home to 64,429 people with a population density of 2,013 inhabitants per sq. km. The islands have a literacy rate of 92.28 per cent, as per the 2011 census. While studies have been made to assess and evaluate the growth of digital financial literacy and inclusion in India, in general, there have not been many UT-specific studies to understand the penetration of digital financial literacy and the popularity of digital payments. Similarly, no specific studies have evaluated the status of digital financial literacy for the Lakshadweep islands. This study aims to address these gaps. The evolution of digital financial literacy and financial services represents an opportunity to reach previously excluded and underserved populations with tailored financial services, and the islands exhibit promise in terms of digital financial literacy and inclusion, as digital means have considerable applicability in the field of education, business, health, tourism, fishing and agriculture. Though there can be apprehensions in the form of consumer risks while engaging in digital financial services, the robust social capital in the form of trust and reciprocity in Lakshadweep and good financial and digital literacy can address these concerns. As per the 2011 census, telephone density was the highest in Lakshadweep where 93 per cent of households owned a telephone set. In 2021, almost all households had one to two mobile phones each. According to the National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) (2019-21), 80 per cent of women in the islands had a mobile phone that they used, and among men, the corresponding figure was 90 per cent. About 56 per cent of women in the islands used Internet, while among men, the proportion was 80 per cent. Though in terms of literacy and digital literacy, Lakshadweep is placed favourably, no serious attempt has been made to evaluate the status of digital financial literacy and inclusion, particularly in the post-pandemic period8. This study attempts to fill this gap. Objectives of the Study: 1. To study and analyse the current status of digital financial literacy and digital financial inclusion of the overall population in the islands with particular emphasis on women. 2. To examine whether there is a digital divide between men and women in the islands. 3. To understand the correlation between digital literacy and digital financial literacy. 4. To study the correlation between digital financial literacy and digital financial inclusion. 5. To assess the opportunities and challenges, including technical, non-technical and gender barriers in terms of digital financial literacy and inclusion. 6. To assess the digital safety and hygiene in the islands. 7. To examine if customers are aware of grievance redressal mechanisms in case of digital financial frauds. Chapter 2 - Relevance of the Study and Literature Review We live in an age where technological advancements over the years have brought financial services to the rich and poor's doorstep but with varying levels of access and reach. The adoption of digitalisation and financial technology, especially FinTech has drastically transformed the delivery of services and products and has quickened the pace of financial inclusion. The COVID-19 pandemic has also accelerated the use of digital financial services and increased the significance of digital financial inclusion. This chapter offers a brief review of the extant literature. 2.1 Financial Literacy, Digital Financial Literacy and Digital Financial Inclusion This study looks into the status of digital financial literacy and digital financial inclusion in the islands. While analysing the correlation between digital financial literacy and digital financial inclusion, it is equally important to look into the correlation between financial literacy and digital financial literacy. Recent studies and research ascertain that digital financial literacy is a combination of digital and financial literacy. This statement is true to a large extent as digital financial literacy is often measured using the metrics of both financial and digital literacy (Lyons and Kass -Hanna, 2021; Azeez and Akthar, 2021 and Ravikumar et al., 2022). 2.2 Financial Literacy The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) aptly defines “financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks but also the skills, motivation and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society and to enable participation in economic life” (Lusardi, 2019). Some define financial literacy as the awareness of financial products and services and the ability to apply financial knowledge and skills to manage financial resources to achieve good financial health (Xiao et al., 2014), while other interpretations define it as an individual’s ability to understand, analyse, manage and communicate personal finance matters. In other words, it refers to a set of skills and knowledge that allows an individual to make informed and effective decisions through their understanding of finances and it also includes the ability to make informed judgments and effective decisions regarding the use and management of money (Prasad et al., 2018 and D’Silva et al., 2019). The literature has suggested five dimensions to evaluate or to measure the real financial literacy levels of a population and these include (1) financial knowledge; (2) financial communication ability; (3) ability to use financial knowledge for decision-taking; (4) real use of instruments (financial behaviour); and (5) financial confidence (Zait and Bereta, 2014). Along with these five dimensions or variables, they also suggest that for every dimension, the measures need to refer to at least four financial areas and they are: (a) personal budgeting; (b) savings; (c) credits; and (d) investments and under this health insurance and pension should also be incorporated. Remund (2010) defines financial literacy as the level of comprehension of basic financial concepts, the ability to make proper decisions in the face of changing economic conditions and having sufficient confidence and ability to manage his/her financial status through planning. Goel and Khanna (2013) define financial literacy as the ability of individuals to make conscious assessments in monetary management and to make efficient decisions accordingly. While financial education programmes have been viewed as a solution to enhance financial literacy, the available literature offers mixed evidence. Some studies support a direct correlation among financial education, financial literacy and positive financial outcomes (Fox, Bartholomae and Lee, 2005; Lsuardi, 2003 and 2011). However, some studies have reported that financial education does not significantly improve the financial knowledge scores (Mandell, 2005 and Willis, 2008). Financial literacy, aimed at improving a person’s knowledge and ability should be tailored to suit different demographics, life stages and learning styles. A one-size-fits-all approach is not going to work in this regard. Studies to determine the financial literacy levels of individuals living in Kayseri province in Turkey revealed a significant relationship between financial literacy and the demographic characteristics of the participants (Aksoylu et al., 2018). Financial literacy is equally important for financial inclusion. When implementing financial inclusion in a diversified country like India, financial literacy plays a greater role (Shetty and Thomas, 2015). The rural areas of India which are backward and the underdeveloped regions of the country pose a challenge in achieving financial inclusion in its true sense (Jagtap et al., 2018). 2.3 Digital Literacy and Digital Financial Literacy Both digital and financial literacy are necessary prerequisites to access and use digital financial services. UNESCO defines digital literacy as the “ability to define, access, manage, integrate, communicate, evaluate and create information safely and appropriately through digital technologies and networked devices for participation in economic and social life,” (UNESCO, 2018). According to OECD, “digital financial services are defined as financial operations using digital technology, including electronic money, mobile financial services, online financial services, i-teller and branchless banking whether through a bank or non-bank institutions” (OECD, 2018). The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) defines digital literacy as “the ability of individuals and communities to understand and use digital technologies for meaningful actions within life situations. Any individual who can operate computer/laptop/tablet/smartphone and use other IT related tools is being considered as digitally literate.” Studies suggest five dimensions in cognitive, technical, and ethical perspectives to define and measure digital literacy, and it includes (1) information literacy; (2) computer literacy; (3) media literacy; (4) communication literacy; and (5) technology literacy (Chetty et al., 2017). Mothkoor and Mumtaz (2021) found that Lakshadweep, Chandigarh and Goa are among the top 10 per cent of digitally literate states and union territories in India. According to them, the rural-urban gap in Lakshadweep in digital literacy was remarkably low at one per cent. 2.4 Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Digital Payments According to the Global Findex Database 2021, the technological revolution and accelerated adoption of digital solutions due to the COVID-19 pandemic are transforming access to finance. In 2021, 71 per cent of the adults in developing economies have a formal financial account, compared to 42 per cent a decade ago. The Global Findex 2021 survey revealed that close to 84 per cent of bank account owners worldwide made or received at least one digital payment. In high-income economies, 98 per cent of account owners did so, compared with 80 per cent in developing economies. The Findex Database shows that the share of adults making or receiving digital payments in developing economies grew from 35 per cent in 2014 to 57 per cent in 2021. Around 39 per cent of the mobile money account holders in Sub-Saharan Africa now use their account for personal savings and more than one-third of adults in developing economies who paid a utility bill from an account did so for the first time after the COVID-19 outbreak, which suggests the positive impact of the pandemic on digital adoption. Studies from India found that COVID-19 positively impacted digital payments (Ravikumar et al., 2022). During the pandemic-induced lockdown, e-Wallet usage jumped by 44 per cent in India, and Paytm and Google Pay emerged as the most popular digital payment apps at the time (PTI 2020, Kumar et al., 2022). Thus, the increase in the adoption and use of digital payment apps can be viewed as a “blessing in disguise” brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic (Kumar et al., 2022). United Payments Interface (UPI) as a mode of mobile banking has made a drastic change among peer-to-peer payments and a lot of recurring cash transactions have moved towards using UPI apps. Since its inception in 2016, UPI transactions have seen exponential growth both in terms of value and volume. Once again, the pandemic acted as a major catalyst for increased digital payment adoption (Chakrabarti and Basu, 2023). Kakade and Veshne (2017) further pointed out that UPI will gradually end cash payments and reduce the circulation of currency notes, and it will eventually lead to a transparent system and a cashless economy. UPI is set to become an efficient alternative to mobile wallets and has made cashless payments faster and easier for millions of people in India (Kandpal and Merhotra, 2019; Barik and Sharma, 2019). However, the need for digital financial services to be made accessible to rural households including daily wage employees, low-income farmers, as well as small-scale industries and companies in the post-pandemic period is being emphasised upon. India’s success of digital financial services would eventually depend on rural India’s transition from a cash-driven to a less-cash and more digital economy (Dilip, 2021). Emphasis should be given towards increasing access to bank credit and life insurance in rural areas, which received a setback following the pandemic (Chavan and Kamra, 2022). 2.5 Factors Affecting the Adoption of Digital Payments Gender was a major factor that affected digital payments adoption. Rasna and Susila (2021) examined the status of UPI payments among the men and women users in rural and urban areas in Kerala and showed a wide gender gap. The study findings showed that only 18.7 per cent of men in rural areas preferred UPI as a mode of payment, while it was only 12.5 per cent for their women counterparts. Further, it was found that in urban areas 37.5 per cent of men prefer UPI, while it was 25 per cent among women respondents. The availably of an easy and fast applications and the convenience of use were the other two factors determining people’s preference towards digital payments. Technological innovations, global research and “shared policy experiences” are also factors that can influence digital adoption across countries, as brought out in the BRICS Digital Financial Inclusion Report of the RBI (2021). The policy initiatives by the governments and central banks in BRICS countries have fundamentally transformed the digital landscape. In India, in particular, the availability of budget smartphones, cheap mobile data prices and government initiatives like Digital India have contributed heavily to digital adoption. Since 2014, many flagship schemes viz., Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY), Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Yojana and Atal Pension Yojana along with Aadhaar and direct benefit transfer schemes have facilitated financial inclusion in general. The Government of India has undertaken major initiatives to bridge the digital divide in the country. In the years, 2014 and 2017, two major schemes (1) National Digital Literacy Mission (NDLM); and (2) Pradhan Mantri Digital Saksharata Abhiyan (PMGDISHA) were implemented by the Government of India with a target to train 52.50 lakh candidates in digital literacy across the country. Under these two schemes, a total of 53.67 lakh beneficiaries were certified. The PMGDISHA was introduced to usher in digital literacy in rural India by covering six crore rural households (one person per household). So far, 6.15 crore candidates have been enrolled and 5.24 crore have been trained, of which around 3.89 crore candidates have been certified under this scheme. In the case of Lakshadweep, the Common Service Centres/ Ashrayas are available in Agatti, Amini, Andrott, Chetlat, Kadmat, Kalpeni, Kavaratti, and Kiltan islands. The data released by MeitY in July 2022 shows that 109 people in the islands registered for training under PMGDISHA, out of which 35 received training. 2.6 Digital Divide The OECD defines the digital divide as the “gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographical areas at different socio-economic levels regarding their opportunities to access information and communication technologies (ICTs) and their use of internet for a wide variety of activities.” The digital divide can be explained as the inequalities between the digital haves and the have-nots in terms of their access to the Internet and the ICTs (Mohammed, 2022). Due to the ever-increasing importance of the Internet and the rapid digital transformation on account of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed has even claimed that the digital divide has the potential to be the “new face of inequality”. “As 21st century banking users entrust the care of one of their most important assets to cyberspace, a seamless, stress-free, and successful experience is essential. Design with users’ success as focus, content understandable by ‘anybody’, supported with demos and help to reduce intimidation, will justify investment online through increased usage by satisfied customers” (Iyengar and Belavalkar, 2010). There exists a wide digital divide in India in the usage of internet and access to digital infrastructure based on gender, age and area of residence (rural and urban). Men generally have greater access to internet and greater ownership of mobile phones (Chandola, 2022). Studies also suggest that urban men in India have better access to Internet and ownership of phones when compared to urban women, rural men and rural women (Chandola, 2022; GSMA Report, 2021; and ICUBE, 2020). While reviewing the literature, it was observed that there is a serious dearth of the developmental literature on Lakshadweep. Thus, the present study hopes to contribute to our understanding of the digital financial literacy and digital inclusion in the islands although it may not be able to fully capture the socio-economic and cultural realities of the islands. Chapter 3 - Socio-Economic Profile of the Lakshadweep Islands This chapter describes the socio-economic profile of the Islands to understand the settings in which the study took place. Lakshadweep is a small island economy (SIE). ';Lakshadweep is one of the few units of administration in the country for which a proper database leading to the construction of the Gross and the Net State Domestic Product is not available'; (Lakshadweep Development Report, 2007). In fact, the Union Territories, namely, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, Ladakh and Lakshadweep do not prepare the estimates of State Domestic Product (SDP) (MOSPI, 2023). This makes it difficult to examine certain critical dimensions of the economic activities in the territory. The policy experts specialising on the UT of Lakshadweep are of the opinion that it would be somewhere around US$ 90-100 million9.  The smallest Union Territory of India has an area of 32 sq. km. Andrott Island has the largest area (4.90 sq. km) while Bitra has the smallest (0.105 sq. km). Minicoy is the longest in terms of land (11 km) and Andrott is the widest (2.4 km). Regarding distance from the mainland, Andrott is the nearest (228 km) while Minicoy is the farthest (398 km). Despite its small geographical landmass, the islands have a large territorial water (20,000 sq. km), an Exclusive Economic Zone (4 lakh sq. km) and a coastal line of about 132 km. The islands have a vibrant local government with a two-tier system of Panchayats at district and village (Dweep) level (Chathukulam and Joseph, 2021). It has one District Panchayat (DP) and ten Village (Dweep) Panchayats (VDPs). 3.1 Major Industries Fisheries and tourism are the major industries in the Islands. According to the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), the islands can harvest up to one lakh metric tonnes of tuna annually. The Lakshadweep tunas are known to have the least histamine content, mainly due to their traditional hook-and-line fishing method and short fishing durations. Since tunas from the islands are considered to be of premium quality, they fetch high prices in national and international markets. In the 2022-23 Union Budget, the UT was allocated Rs.9.5 crore (US$ 1.24 million) for tourism development. As per the Social Progress Index (SPI), 2022, the islands scored 65 for its remarkable performance across components like personal freedom and choice, shelter, drinking water, and sanitation. The coastal and tropical environment of Lakshadweep makes it viable for commercial cultivation of coconut. Roughly one-fourth of coconuts produced in the islands are used for domestic consumption. Copra, coconut oil, coir and coir products, coconut inflorescence sap (neera) and coconut jaggery are the major traditional coconut-based enterprises in the islands. Apart from fish and coconuts, everything else is imported and sourced from mainland, especially Kerala. The islanders depend on ships for travelling and to get provisions. The erratic nature of the ship schedule and ticketing often affects students and islanders. Ships remain the only mode of transport for most islanders, while helicopters being mostly used as air ambulances. There are flights to Agatti, but it is mostly helpful to the residents of Agatti and Kavaratti. The passengers are ferried from Agatti to Kavaratti in vessels but travel to other islands from Kavaratti may take a few days depending on the vessel schedule. 3.2 Bank and ATM Density in the Islands The team visited 11 public sector banks (PSBs) operating in the Islands. During the field visit, it was noticed that these banks were located within a maximum distance of 3-4 kilometres in all the islands except Bitra which has no bank. Bitra, which has a total population of 271 (as per census, 2011) has one ATM. Kavaratti, which has a population of 11,221 people has six ATMs and two PSBs. Minicoy with a total population of 10,447 people has two PSBs and two ATMs. Andrott with a population of 11,191 has one ATM and one bank operating in the islands. Amini and Agatti with a population of 7,661 and 7,566, respectively have one bank and one ATM each. Kadmat with a population of 5,404, Kalpeni with 4,419 people and Kiltan with 3,946 people have one bank and one ATM each. Chetlat with a total population of 2,347 has one bank and one ATM. In addition, most of the residents in Bitra also depend on the bank and ATM operating in Chetlat. 3.3 Island-wise Profile The island-wise profile of the ten islands is summarised in the tables below: | Table 3.1: Island-wise Demographic Profile of Lakshadweep | | Island | Population | Number of men | Number of women | Number of households | Population density

(per square km.) | | Agatti | 7521 | 3850 | 3671 | 1328 | 2778 | | Amini | 7661 | 3829 | 3832 | 1375 | 2881 | | Andrott | 11191 | 5500 | 5691 | 1806 | 2312 | | Bitra | 271 | 154 | 117 | 75 | 2198 | | Chetlat | 2347 | 1172 | 1175 | 526 | 2255 | | Kadmat | 5389 | 2676 | 2713 | 1061 | 1727 | | Kalpeni | 4419 | 2324 | 2095 | 934 | 1548 | | Kavaratti | 11210 | 6171 | 5039 | 2249 | 2659 | | Kiltan | 3946 | 2012 | 1934 | 778 | 2363 | | Minicoy | 10477 | 5366 | 5081 | 1442 | 2163 | | Source: Census 2011. |

| Table 3.2: Island-wise Age profile of the Selected Respondents | | Island | Percentage Share of Persons | | Aged Less than 5 Years | Aged between 5 and 15 Years | Aged between 15 and 40 Years | Aged between 40 and 65 Years | Senior Citizens | | Agatti | 0 | 14 | 50 | 33 | 3 | | Amini | 0 | 10 | 53 | 32 | 5 | | Andrott | 3 | 14 | 55 | 24 | 4 | | Bitra | 4 | 21 | 51 | 22 | 2 | | Chetlat | 5 | 15 | 51 | 26 | 3 | | Kadmat | 2 | 14 | 49 | 28 | 7 | | Kalpeni | 2 | 19 | 56 | 20 | 3 | | Kavaratti | 2 | 10 | 50 | 31 | 7 | | Kiltan | 1 | 12 | 54 | 28 | 5 | | Minicoy | 2 | 16 | 41 | 31 | 10 | | Source: Field Data. |

| Table 3.3: Socio-economic profile10 | | Island | Literacy rate (per cent) | Share of persons with (per cent) | | Total | Men | Women | Primary & Secondary education | Higher Secondary education | Graduation and above | | Agatti | 92 | 92 | 90 | 51 | 35 | 14 | | Amini | 89 | 96 | 82 | 51 | 27 | 18 | | Andrott | 91 | 95 | 86 | 45 | 32 | 18 | | Bitra | 97 | 99 | 95 | 55 | 33 | 10 | | Chetlat | 92 | 95 | 89 | 50 | 31 | 17 | | Kadmat | 95 | 97 | 93 | 59 | 28 | 8 | | Kalpeni | 95 | 98 | 92 | 42 | 24 | 27 | | Kavaratti | 92 | 95 | 87 | 44 | 27 | 20 | | Kiltan | 89 | 93 | 86 | 52 | 35 | 11 | | Minicoy | 93 | 95 | 90 | 69 | 21 | 5 | | Sources: Census 2011 and Field Data. | Occupational, Income and Other Details about the Islands11 3.3.1. Agatti People on this island speak Malayalam, English and Tamil. Fishing, coir, copra and tourism are the major industries. An airport exists on this island and thus it serves as a virtual gateway to the remaining islands. It is also one of the most accessible islands in the UT. More than one-fourth of the households were headed by those engaged in other professions, while one-fifth were fisherfolk. The remaining were managed by retired employees, homemakers, farmers, government employees, business-persons and teachers. Very few were self-employed and unemployed. In the case of total annual income, more than 80 per cent were low-income households with an annual income between Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh and the remaining were middle-income households (between Rs.3 lakh and Rs.10 lakh). 3.3.2. Amini Apart from coconut cultivation, tourism and fishing; handicrafts are a major industry. Walking sticks made with tortoise and coconut shells are popular among the tourists. Stone engraving is another major attraction. Regarding the occupational status of family members, more than one-third of the respondents were self-employed, followed by 28 per cent homemakers. The remaining were teachers, business-persons, seafarers, fisherfolk, government employees, retirees and students. When it comes to the annual income of the households, 76 per cent were low-income households (Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh) and one-fifth were middle-income households (Rs. 3 lakh to Rs. 10 lakh). 3.3.3. Andrott Fishing, coconut cultivation and coir twisting are the major occupations. Tourism is also an emerging industry. More than 40 per cent of the households were headed by homemakers, while more than one-fourth of the homes were headed by self-employed persons. One-tenth of the houses were headed by government employees and retirees each. The remaining households were managed by teachers, business and fisher folk. In the case of total annual income, more than 80 per cent were low-income households (Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh) and one-fifth were middle-income households (Rs.3 lakh to Rs.10 lakh). 3.3.4 Bitra About 43 per cent were managed by fisherfolk, while retired employees head more than one-fourth. Less than one-fifth of the households were headed by teachers and self-employed. Regarding the total annual income, more than 70 per cent were low-income households (Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh) and one-fourth were middle-class households with an annual income between Rs.3 lakh to Rs.10 lakh. 3.3.5 Chetlat Coir twisting is one of the chief occupations of the people on the island. Manufacturing mats and weaving coconut leaves are common activities found here. More than one-fourth of the houses were headed by persons engaged in other professions and homemakers. While one-fifth of the households were managed by retirees, another one-fifth by self-employed persons. Less than 10 per cent of the households each were headed by homemakers, government employees and teachers. A small share of households was headed by fisherfolk and unemployed. More than 80 per cent were low-income households (Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh), while less than one-fifth were middle-income households (Rs. 3 lakh to Rs.10 lakh). 3.3.6 Kadmat Kadmat is at the centre of the archipelago. Fisheries is the main economic activity along with agriculture on a small-scale basis. Tourism is another major attraction on the island. In the case of the main occupation of the head of the households, more than one-third of the households were headed by homemakers and one-fourth were headed by self-employed persons. Government employees constitute 11 per cent of the households and another 11 per cent were headed by unemployed persons. Close to 10 per cent of the households were headed by retired employees and those engaged in other professions each. A negligible per cent of the houses were headed by fisherfolk. Regarding the total annual income, 80 per cent were low-income households (Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh) and less than one fifth have annual income above Rs.3 lakh to Rs.10 lakh. 3.3.7 Kalpeni Regarding the occupational status of the main head of the households, more than 40 per cent were headed by homemakers, 16 per cent were headed by retirees while another 16 per cent were by individuals engaged in other professions. The remaining share of the households was headed by teachers, fisherfolk and the unemployed. Regarding the annual family income, more than half were low-income households (Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh), while more than one-third were in middle income category. 3.3.8 Kavaratti Kavaratti is the capital of the Lakshadweep. The island has been selected as one of the 100 Indian cities to be developed as a smart city under the Smart Cities Mission. More than one-fourth of the households were headed by homemakers and another one-fourth by retirees. One fifth of the households were headed by government employees, while less than 15 per cent were looked after by those engaged in other professions. Less than 10 per cent of the households are headed by fisher folk and business-persons each. A negligible per cent of houses were run by seafarers and doctors. Regarding the total annual income of the households, more than half are low-income households, more than one-third are middle income households and a negligible per cent of the households have an annual income above Rs.20 lakh. 3.3.9 Kiltan Kiltan is located in the northern group of the archipelago. Regarding the occupational status of the main head of the households, 31 per cent were headed by self-employed persons, while one-fourth by retired employees. Less than one fifth of the households were headed by homemakers and government employees each and the remaining by teachers, fisherfolk and business-persons. In case of the total annual income, 75 per cent were low-income households (Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh). The remaining were middle income households with a total annual income in the range of Rs.3 lakh to Rs.10 lakh. 3.3.10 Minicoy The island has a unique culture that is different from the rest of the nine islands. The island comprises 10 villages, which are called Athiris, each presided by a Moopan and a Moopathi. Tuna fishing is a major activity and there is a Tuna canning factory and facilities for boat building. It also has one of the oldest lighthouses. Regarding the main occupation of the head of the households, more than half of the households were headed by seamen. Less than 10 per cent each were headed by homemakers, government employees and retirees. Half of the households have an annual income between Rs.3 lakh and Rs.10 lakh, while one-third were low-income households in the range of Rs.10,000 to Rs.2 lakh and 12 per cent above 20 lakhs. 3.4 Island-wise Selection of Sample for the Study The team selected a sample size consisting of 1,024 households with 4,598 family members (Table 3.4). From these 4,598 family members, 1,550 respondents were men and 1,886 were women (Table 3. 5). | Table 3.4: Island-wise Sample Size of the Households | | Island | Total Households* | Targeted Number of Households (Sample size) | Total Number of Selected Households | Total Number of Family Members | | Agatti | 1328 | 115 | 111 | 392 | | Amini | 1375 | 119 | 117 | 502 | | Andrott | 1806 | 156 | 157 | 712 | | Bitra | 75 | 6 | 7 | 49 | | Chetlat | 526 | 45 | 49 | 255 | | Kadmat | 1061 | 92 | 105 | 413 | | Kalpeni | 934 | 81 | 82 | 318 | | Kavaratti | 2249 | 194 | 197 | 1042 | | Kiltan | 778 | 67 | 74 | 406 | | Minicoy | 1442 | 125 | 125 | 509 | | Total | 11574 | 1000 | 1024 | 4598 | Note: * Total Households as per Census, 2011.

Source: Field Data. |

| Table 3.5: Island-wise Details of Number of Selected Respondents | | Island | Men | Women | Students | Self-Help Groups | Business Units | Banks | Schools | | Agatti | 150 | 152 | 67 | 30 | 31 | 1 | 4 | | Amini | 145 | 178 | 73 | 30 | 32 | 1 | 4 | | Andrott | 209 | 302 | 68 | 34 | 31 | 1 | 6 | | Bitra | 15 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | | Chetlat | 85 | 99 | 28 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 2 | | Kadmat | 141 | 182 | 41 | 24 | 34 | 1 | 5 | | Kalpeni | 135 | 164 | 50 | 24 | 24 | 1 | 2 | | Kavaratti | 370 | 391 | 74 | 32 | 38 | 2 | 6 | | Kiltan | 163 | 164 | 49 | 14 | 20 | 1 | 2 | | Minicoy | 137 | 234 | 32 | 31 | 29 | 2 | 5 | | Total | 1550 | 1886 | 489 | 232 | 252 | 11 | 37 | | Source: Field Data. | The team surveyed 489 students, conducted interviews with 232 SHGs and 252 business units. A total of 11 banks and 37 schools were also interviewed (Table 3.5). Chapter 4 - Digital Financial Literacy and Inclusion in the Surveyed Islands:

An Analysis of Users This chapter analyses the island-wise financial and digital financial inclusion. It also discusses the banking and digital hygiene habits. The first section offers an island-wise comparison, while the second section offers a detailed analysis of each island. Financial inclusion is defined as access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their banking needs including transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance for individuals, institutions or businesses, which are delivered in a responsible and sustainable manner (World Bank, 2020). Access to a transaction account is the first major step towards broader financial inclusion, since a transaction account allows people to not only store and save money but also send and receive payments. In a way, a transaction account serves as a gateway to other financial services, so ensuring that people have an operational bank account is necessary in measuring financial inclusion and basic financial literacy. Without basic financial literacy and inclusion, achieving digital financial inclusion is next to impossible. 4.1 Men 4.1.1 Type of Accounts All respondent men had operational bank accounts. While 98 per cent had savings accounts, only a small per cent had current and joint accounts (Figure 4.1). All the respondent men in Bitra, Kadmat and Kalpeni had savings accounts. These three islands had the highest number of operational savings accounts. Chetlat had the lowest percentage of savings accounts at 76 per cent (Figure 4.2). 4.1.2 Operation of Bank Accounts Financial inclusion is not limited to having access to banks and bank accounts alone, the skill and efficiency to operate and manage one’s bank account also matters as it is equally necessary to carry out even the basic banking functions. In terms of operating bank accounts, it was found that 92 per cent men could operate their accounts on their own (Figure 4.3). Only in Kalpeni, 100 per cent of men could do so (Figure 4.4). In case of Agatti and Amini, the corresponding figure was 98 per cent each and in Kadmat, it was 97 per cent. On the other hand, 82 per cent in Kiltan and 68 per cent in Andrott could operate their bank accounts by themselves.

4.1.3 Purpose of Operating Bank Accounts Regarding the purpose of operating the accounts, 93 per cent men used their accounts for personal savings while remaining used them for educational purposes and for receiving direct benefit transfers (Figure 4.5). Educational purposes in Lakshadweep context refers to accounts created for receiving assistance for mid-day meal. All men in Bitra, Kiltan, Kalpeni and Minicoy islands operated their accounts to keep personal savings. Apart from these four islands, the men in Kadmat (99 per cent) and Agatti (94 per cent) also used their accounts for the same purpose. All these six islands were way above the average of 91 per cent. (Figure 4.6). 4.1.4 Possession of ATM Cards ATMs are one of the earliest forms of digital banking. In India, it is still the most popular form of digital banking and it has the potential to accelerate digital financial inclusion even in remote areas like Lakshadweep. Among the total men respondents, it was found that 95 per cent had their own ATM cards (Figure 4.7). Bitra island had no banks but had an ATM operating on the island. It was observed that 100 per cent of the men in Bitra had ATM cards. Kiltan had the second highest at 99 per cent (Figure 4.8). 4.1.5 Mode of Operating the Bank Accounts About 91 per cent of men used ATM cards, while 70 per cent visited the bank and 58 per cent used mobile banking. A minuscule share of less than 2 per cent used Internet banking (Figure 4.9; Appendix 1.1). 4.1.5.1 Use of Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) As previously mentioned, the possession of ATMs was quite ubiquitous in the islands. The usage of ATMs in the islands too was prevalent. About 91 per cent used these cards. In Bitra, the usage was universal with all respondent men using it given the absence of a bank branch (Figure 4.10). 4.1.6 Frequency of Operating the Bank Accounts More than 50 per cent of men were found to be operating their bank accounts monthly, followed by 22 per cent weekly and less than one-fifth of them once in two months (Table 4.1). | Table 4.1: Frequency of Operating Bank Accounts among Men in Lakshadweep | | Frequency | Men | | Number | Percentage | | Weekly | 347 | 22 | | Monthly | 784 | 51 | | Once in Two Months | 293 | 19 | | Relatively Less | 115 | 7 | | No Answer | 8 | 1 | | Not Using | 3 | 0 | | Total | 1550 | 100 | | Source: Field Data. | 4.1.7 Familiarity with Digital Financial Transactions The familiarity and awareness regarding digital financial transactions are necessary prerequisites to operate and use digital payment apps. Out of the total men, 916, that is more than half (59 per cent) were found to be familiar with digital financial transactions (Figure 4.11). Kadmat, Kavaratti, Chetlat, Andrott and Agatti islands had the highest number of men familiar with digital transactions (Figure 4.12). Most men admitted that it was because of the potential of digital transactions to save time and money (Appendix 1.2).

4.1.8 Awareness of Digital Hygiene Habits We examined the digital hygiene habits among the respondents who were familiar with digital financial transactions. The digital hygiene habits assessed here included whether they use public internet connections (which are generally risky); closed digital payment apps after doing transactions; and used secure passwords. Only 43 per cent were familiar with these digital hygiene habits (Appendix 1.3). In the Islands, one-fourth of the men used public internet connections (Figure 4.13). The usage was particularly rampant among men in Agatti, Kiltan and Chetlat (Appendix 1.3). Importantly, about 85 per cent of the men closed apps after transactions (Figure 4.13). It was seen that 65 per cent of men followed digital hygiene habit of using secure passwords. 4.1.9 Barriers of Digital Financial Inclusion Slow network was found to be a major problem in Lakshadweep, and it was the first and foremost barrier for digital financial inclusion (Appendix 1.3). Close to 90 per cent admitted that a slow network was a major problem behind adopting digital financial inclusion. Although inadequate Internet connection impedes wide-spread adoption of digital payments, numerous other factors, such as lack of perceived necessity, safety, and confidentiality apprehensions also deterred people from utilising digital payments. 4.2. Women 4.2.1 Type of Accounts All respondent women had bank accounts. About 97 per cent were found to have savings bank accounts and a small per cent have current accounts and joint accounts (Figure 4.14). Almost 100 per cent in Amini, Bitra, Kadmat and Kalpeni had savings bank accounts (Figure 4.15). The access to deposits was the lowest in Chetlat, 71 per cent. 4.2.2 Operation of Bank Accounts Among the total women respondents, 71 per cent operated their accounts by themselves, which was much lower than that for men (Figure 4.16). The remaining three per cent women respondents did not answer. Kalpeni had the highest number of accounts managed by women on their own at 94 per cent. Agatti had the second highest. Andrott had the least number of accounts operated by women on their own at 44 per cent (Figure 4.17). 4.2.3 Purpose of Operating Bank Accounts Among the total women, 90 per cent operated their accounts for personal savings. When it comes to island-wise statistics, Agatti and Kalpeni were at the top with 100 per cent (Figure 4.18). Less than 10 per cent of the women used their accounts for educational purposes and also for receiving DBTs. 4.2.4 Possession of ATM Cards It was observed that 85 per cent of the women have ATM cards in the islands (Figure 4.19). Regarding island-specific analysis, Bitra had the highest i.e., 100 per cent of women using ATM cards and Amini had the least (Figure 4.20).

4.2.5 Modes of Operating the Accounts Following the widespread possession of ATM cards, most women (72 per cent) used these cards for operating their accounts, while 67 per cent visited the bank. The usage of mobile and Internet banking were the lowest (Figure 4.21). The maximum number of women who used ATM cards were in Bitra (100 per cent) (Figure 4.22). Bitra also reported the highest incidence of using BCs (Appendix 1.4).

4.2.6 Frequency of Operating the Accounts Among women respondents, the frequency of operating accounts was much lower than men. More than one-third of them operated bank accounts only on a monthly basis. The weekly operation of accounts was less common among women in the Islands (Table 4.2). | Table 4.2: Frequency of Operating Accounts among Women in Lakshadweep | | Frequency | Women | | Number | Percentage | | Weekly | 105 | 6 | | Monthly | 685 | 36 | | Once in Two Months | 504 | 27 | | Relatively Less | 480 | 25 | | No Answer | 88 | 5 | | Not Using | 24 | 1 | | Total | 1886 | 100 | | Source: Field Data. | 4.2.7 Familiarity with Digital Financial Transactions The knowledge of digital financial transactions was much less among women; only 36 per cent were familiar with it (Figure 4.23). Studies have shown that men are likely to be more familiar with digital technology and digital transactions than women (Shree et al., 2021; Shaheed, 2022; Chakrabarti and Basu, 2023). Prasad et al. (2018), who mapped digital financial literacy in the households of Udaipur in Rajasthan, found that men are more familiar with digital financial platforms and more competent in using digital instruments and technologies than women. There was a wide variation across islands in the familiarity with digital financial transactions with Kadmat and Chetlat leading in this regard (Figure 4.24). Similar to men, 93 per cent of the women admitted that doing so saved their time and money (Appendix 1.5).

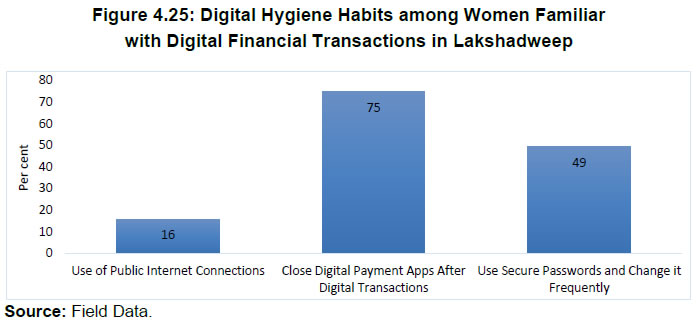

4.2.8 Awareness of Digital Hygiene Habits It was observed that only one-fifth of the women respondents have heard about digital safety measures and precautions to undertake while making digital transactions. This general awareness was found high among the women in Kadmat (Appendix 1.6). As compared to men, very few women (only 16 per cent) used public Internet connections. However, the awareness about digital payment apps was much more prevalent, as 75 per cent of the women close after doing digital financial transactions (Figure 4.25). In the Islands, 49 per cent of the women used secure passwords and changed them frequently. Similar to men, for women too, the slow network was a major barrier for digital financial transactions. Apart from this, digital failures, security and privacy concerns also impeded digital financial transactions (Table 4.3).

| Table 4.3: General Barriers for Digital Financial Transactions in Lakshadweep | | Sl. No. | Other Major Barriers | Percentage of respondents | | | Poor Internet connectivity | 99 | | 1 | Fear of Digital Transaction Failures | 97 | | 2 | Security Concerns | 92 | | 3 | Privacy Concerns | 90 | | 4 | Lack of Perceived Need | 85 | | Source: Field Data. | 4.3 Students The majority of students had joint bank accounts (Appendix 1.7). Though the RBI has allowed banks to offer savings accounts to children above the age of 10 years to be operated by themselves independently, but the islanders had less awareness in this regard. Meanwhile, students studying Class 8 to 12 have Sanchayika Savings accounts (Individual accounts) opened by their schools in the post office. The students were given pass books but there was no facility for ATM cards, Internet and mobile banking. Most students i.e., 79 per cent visited the bank branch for transactions and 27 per cent used ATM cards (Figure 4.26). A very low number of students used Internet and mobile banking. The student community had a major concern about the existing poor Internet connectivity, which posed serious challenges to online education and digital financial transactions. 4.4 SHGs Except for the SHGs in Bitra, all others had bank accounts. All SHGs in the nine islands visited their bank branch to do financial transactions. In Bitra, the SHG groups depended on a cooperative society on the island. None of them used ATM cards, Internet banking or mobile banking as they all had joint accounts. Importantly, the awareness about various relevant governmental schemes was limited among SHGs; for instance, except for Chetlat and Kavaratti, none of the members in these groups were aware of PMMY. 4.5 Business Groups Business groups in the context of Lakshadweep includes small and medium scale shops selling provisions and other essential items, textile shops, jewellery shops, beverage manufacturing units, fish processing units, furniture shops, coir-yarn production centres, fibre curling units, wood-based products manufacturing MSMEs, coconut defibring units, cooperative society supermarket, shops selling electronic items, recharge shops and medical shops. About 94 per cent of business groups had bank accounts. While 92 per cent of the groups had SB accounts, five per cent had current accounts and a negligible per cent had OD (Overdraft) accounts (Appendix 1.9). Among those groups with bank accounts, most (92 per cent) visited the branch for transactions. The penetration of ATM cards and mobile banking was also fairly common among these groups (Figure 4.27). There was a wide variation in the use of internet and mobile banking among business groups across various islands, while the usage ATM cards was commonplace across all islands (Figure 4.28). 4.6 Financial and Digital Financial Inclusion in Educational Institutions (Schools) in the Islands All educational establishments in the islands had bank accounts. There was basic financial literacy among the school authorities and staff. However, there was little or no awareness or inclusion through digital modes among the selected educational establishments. Most educational establishments were at ease and comfort of using physical modes like bank branches. The poor network connectivity also acted as a discouragement in adopting digital services. The school authorities and staff had less awareness regarding the Money Smart School Programme (MSSP), Financial Education Training Programme (FETP), SAKSHAM Centres and Financial Literacy Centres12. In this regard, efforts should be taken to strengthen digital financial literacy among the school authorities and the concerned stakeholders who are at the forefront of transforming the country through Digital India. Policies and schemes to promote and encourage the use of digital financial services and cashless payments should be introduced in educational establishments in the islands. 4.7 Levels of Financial Literacy, Digital Literacy, Digital Financial Literacy and Digital Financial Inclusion in the Islands It is evident from the preliminary data collected from the Islands that there is a high level of financial literacy and digital financial inclusion in Lakshadweep island (Table 4.4). | Table 4.4: Island-wise Details of Financial Literacy, Digital Literacy and Digital Financial Literacy | | Island | Financial Literacy (%) | Digital Literacy (%) | Digital Financial Literacy (%) | Financial Inclusion (%) | Digital Financial Inclusion (%) | | Agatti | 96 | 94 | 78 | 95 | 77 | | Amini | 94 | 90 | 75 | 93 | 74 | | Andrott | 93 | 92 | 82 | 92 | 67 | | Bitra | 97 | 94 | 89 | 96 | 85 | | Chetlat | 95 | 90 | 88 | 93 | 69 | | Kadmat | 95 | 90 | 85 | 94 | 66 | | Kalpeni | 97 | 95 | 74 | 95 | 73 | | Kavaratti | 98 | 96 | 88 | 96 | 80 | | Kiltan | 96 | 94 | 78 | 95 | 73 | | Minicoy | 98 | 96 | 85 | 97 | 82 | Note: Prior to the survey and distribution of the questionnaire, the research team conducted a focused group discussion with the men, women, students, SHG members, business workers and owners in the Islands to understand their attitudes towards banking and assessed their banking habits in general. During the discussion, we noticed that majority of them use smartphones, and they were attending calls and sending messages without seeking help from the person sitting next to them. They are also familiar with basic banking and digital banking terminologies. They could tell the names of the digital payment apps and social media apps they have installed on their phones. Based on the observations and inputs we got from the respondents, we developed a 10-point Likert scale to estimate their knowledge levels in terms of financial, digital literacy and digital financial literacy (Appendix 1.13). In addition, the responses to the questions in the questionnaire also helped in getting an accurate picture of the levels of financial, digital and digital financial literacy. With the findings that emerged from these processes, these percentages listed in the table were worked out.

Source: Field Data. |

| Table 4.5: Correlation Matrix of Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion in Lakshadweep | | Item | Financial Literacy | Digital Literacy | Digital Financial Literacy | Financial Inclusion | Digital Financial Inclusion | | Financial literacy | 1.0000 | | | | | | Digital literacy | 0.8294 | 1.0000 | | | | | Digital financial literacy | 0.2642 | 0.0310 | 1.0000 | | | | Financial inclusion | 0.9569 | 0.8250 | 0.2359 | 1.0000 | | | Digital financial inclusion | 0.7601 | 0.7068 | 0.2538 | 0.8212 | 1.0000 | | Source: Calculated from survey data. | The correlation matrix in Table 4.5 shows that there was a strong correlation between financial literacy and financial inclusion; financial inclusion and digital financial inclusion; digital literacy and financial literacy; digital literacy and financial inclusion; and financial literacy and digital financial inclusion. 4.8 Logistic Regression Analysis In order to empirically quantify the determinants of digital financial literacy and digital financial inclusion of the surveyed respondents, we used a logistic regression model. Model I was estimated taking digital financial literacy (defined as basic awareness about digital financial applications/platforms) as the dependent variable, while Model II was based on digital financial inclusion (defined as whether the respondents used ATM cards or not). The results were on expected lines (Table 4.6). First, gender was a statistically significant determinant under both models but with a negative coefficient, indicating weaker digital financial literacy and inclusion for women as compared to men. Second, age also emerged as a statistically significant determinant of both digital financial literacy and inclusion, with younger population having a greater probability of being aware and being the users of digital financial modes. Third, income was a statistically significant determinant of digital financial inclusion. Fourth, the source of employment did not make a major difference to the extent of digital financial literacy among the respondents. Irrespective of whether the respondents were self-employed, wage-employed or governmental employees, they exhibited digital financial literacy. | Table 4.6 Determinants of Digital Financial Literacy and Inclusion | | Variable | Model I | Model II | | Digital Financial Inclusion | Digital Financial Literacy | Gender

(Women=1, otherwise=0) | -1.2932***

(0.0355) | -0.7459***

(0.0415) | Government employment

(Govt employee=1, otherwise=0) | -0.2381

(0.2881) | 0.8326***

(0.4373) | Self-employment

(Self-employed=1, otherwise=0) | -0.9760***

(0.0619) | 0.1713*

(0.1353) | Wage employment

(Wage employed=1, otherwise=0) | -0.1123

(0.2451) | 0.2511*

(0.2181) | | Income | 0.00002***

(0.0000002) | 0.00003

(0.0000001) | | Age | -0.1120***

(0.0048) | -0.0441***

(0.0031) | | Constant | 6.8475***

(278.7857) | 2.3820***

(1.8211) | | Number of observations | 3436 | 3436 | | Wald χ2 | 517.33 | 311.97 | | Pseudo R2 | 0.2676 | 0.0884 | Note: (i) ***, **, * denotes significance at 1 per cent, 5 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively.

(ii) Figures in brackets indicate robust standard errors.

(iii) Income is represented in rupee terms.

Source: Calculated from field data. | 4.9 Conclusion It was observed in the study that there is a high level of financial inclusion among the surveyed men and women in the Islands as all of them have operational bank accounts, and the majority of them use SB accounts. Among the men and women, more than 80 per cent operated their accounts independently. Though no gender gap existed in terms of account ownership, there was a considerable difference in various modes used for operating the accounts between men and women in the islands. While more than 90 per cent of men operates their accounts by themselves, the corresponding figure among women stands at 70 per cent. Similarly, 70 per cent of men visited the bank to do financial transactions whereas only 65 per cent of women did the same. In the case of ATM cards, 91 per cent men used them but only 73 per cent women made use of it. Bitra is the only island with 100 per cent of men and women using ATM cards. There were two Financial Literacy Centres operating in Andrott and Minicoy islands. The research team visited these Centres and learned that the SHG members are attending these centres. The dominance of men was visible even in the case of digital financial inclusion, including familiarity with digital financial transactions and hygiene habits, and the same was evident in the digital mode of transactions. Similarly, the usage of ATM cards and mobile banking was higher among men than women. Internet banking had only a few takers, while more than one-third of the respondents were into mobile banking in the Islands. In the case of mobile banking, more than half of the men in the Islands used it, while close to one-fourth of the women admitted to using the same. Regarding island-wise analysis, the highest number of men using mobile banking was in Agatti with 80 per cent followed by Kavaratti at 77 per cent. In the case of women, Agatti and Kavaratti were at the top spot with 53 per cent and 52 per cent, respectively. The usage of digital transactions among students and SHG groups was relatively less (largely because they operated joint bank accounts). The business groups were more into digital payments. Since those engaged in business frequently travel to the mainland, they were not much deterred by the network connectivity issues. There was a strong correlation between financial literacy and financial inclusion as well as between financial literacy and digital financial inclusion in the islands. The logistic regression model showed a weaker digital financial literacy and inclusion for women as compared to men. Income was also found to be a significant determinant of digital financial inclusion. Though the poor Internet connectivity served as a barrier towards adopting digital payments on a full-fledged basis, a variety of factors including fear of transaction failures, lack of perceived need, security, and privacy concerns also were found as the major bottlenecks preventing people in the islands from becoming part of a digitally inclusive society. The COVID-19 pandemic played a significant role in convincing even people living in remote islands like Lakshadweep to adopt digital payments despite the poor network connectivity posing hurdles. To further the digital financial inclusion, camps could be organised under the aegis of the National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE) and Centre for Financial Literacy and Service Delivery (CFL & SD), also known as (SAKSHAM CENTRES) especially among SHG groups and students. In addition, training programmes and workshops on digital literacy and digital financial literacy, focusing on women and children, could also be implemented through NCFE, CFL, and SD. Chapter 5 - Digital Financial Literacy and Inclusion in the Islands:

An Analysis of Service Providers 5.1 Island-wise Bank Details The team visited 11 PSBs in the islands to understand the role of these financial institutions in educating and empowering their customers to use digital banking and helping them to be a part of the digital financial inclusive society. The team assessed the competency of the bank staff in educating their customers on various modes of operating the bank accounts including digital transactions and in providing awareness of digital hygiene habits. The team discussed the nature of training the bank staff has received in handling digital financial transactions and mitigating cyber security threats. Establishing bank branches in remote locations and ensuring their smooth functioning is a challenge in India and other parts of the world. However, Lakshadweep has proven to be a good role model in this regard. The feasibility of the banks in the islands should be viewed through the lens of “need-based framework”. Banks and their employees in Lakshadweep should be given the credit for bringing majority of the people living in this remote island into the fold of financial inclusion and mainstream economy. Banks in the islands have played a greater role in fostering financial literacy and financial inclusion. They have played an instrumental role in inculcating banking habits, financial discipline and economic prudence into the lives of people living in Lakshadweep and the banks are able to enjoy the trust of the islanders. The banks are able to provide adequate services to their customers and the islanders are satisfied with them which is evident from their customer base in the island, and which has positively influenced the profitability of these institutions. At a time when rural banking is posing a challenge in various parts of India, the popularity and trust enjoyed by the banks in Lakshadweep are inspiring. While the absence of private banks in Lakshadweep is a limitation to some extent, the fact that people living in remote locations have been able to place their trust in PSBs is a good achievement. There are a total of 90,572 account holders in the selected PSBs in the islands and close to 90 per cent of them are active bank account holders (Table 5.1). This indicates that majority of the population are actively utilising bank services in the islands. | Table 5.1: Island-wise details of Customer Profile in Select PSBs | | Island | Bank | No. of Account Holders in the Bank Branch | No. of Active Account Holders | No. of ATM Card Holders | No. of Banking Customers who Had Activated Internet Banking | No. of Active Users who Were Using Internet Banking | No. of Customers Using Mobile Banking | | Agatti | PSB1 | 9238 | 8138 | 6297 | 555 | 555 | 521 | | | | (88) | (68) | (6) | (6) | (6) | | Amini | PSB2 | 10118 | 10118 | 7411 | 548 | 548 | 1248 | | | | (100) | (73) | (5) | (5) | (12) | | Andrott | PSB3 | 14325 | 12139 | 8637 | 705 | 705 | 884 | | | | (85) | (60) | (5) | (5) | (6) | | Chetlat | PSB4 | 3472 | 3004 | 2448 | 426 | 2 | 279 | | | | (87) | (71) | (12) | (0) | (8) | | Kadmat | PSB5 | 7753 | 7753 | 4741 | 550 | 550 | 447 | | | | (100) | (61) | (7) | (7) | (6) | | Kalpeni | PSB6 | 7000 | 6400 | 4500 | 300 | - | 440 | | | | (91) | (64) | (4) | (0) | (6) | | Kavaratti | PSB7 | 4717 | 3268 | 3099 | 568 | 390 | 2801 | | | | (69) | (66) | (12) | (8) | (59) | | Kavaratti | PSB8 | 11836 | 9738 | 7371 | 795 | 795 | 559 | | | | (82) | (62) | (7) | (7) | (5) | | Kiltan | PSB9 | 5194 | 5194 | 4287 | 447 | 447 | 959 | | | | (100) | (83) | (9) | (9) | (18) | | Minicoy | PSB10 | 5700 | 4800 | 4000 | 800 | 800 | 800 | | | | (84) | (70) | (14) | (14) | (14) | | Minicoy | PSB11 | 11219 | 10812 | 8209 | 949 | 949 | 4635 | | | | (96) | (73) | (8) | (8) | (41) | | Total | 90572 | 81364

(90) | 61000

(67) | 6643

(7) | 3381

(4) | 13573

(15) | Note: Figures is parenthesis are in per cent.

Source: Field Data. | Though India has made remarkable progress in bank account ownership, with 80 per cent of the population having bank accounts, one of the concerning issues has been the high percentage of inactive accounts, which stands at 38 per cent (Chakrabarti and Basu, 2023). This indicates that a significant portion of the population in the country remains excluded from actively utilising bank services. Compared with the rest of India, a remote island like Lakshadweep is far ahead, especially in terms of basic financial inclusion, with 90 per cent active bank accounts. Among the selected banks in the islands, close to 67 per cent of the account holders have an ATM card issued by the banks. It can be said that ATM is the most popular and accepted form of digital banking service in the islands. Only 7 per cent of the bank account holders have activated Internet banking, while only 3 per cent use it. The technicality involved in Internet banking and limited network connectivity were cited as the major reasons behind less preference and use of internet banking. Meanwhile, mobile banking enjoys a small popularity, with close to 15 per cent of the customers using it. Details regarding type of accounts in the selected PSBs and staff structure are given in Tables 5.2 and 5.3, respectively. | Table 5.2: Details of Jan Dhan Accounts, PMMY Accounts in PSBs in Lakshadweep | | Island | Bank | No. of Jan Dhan Accounts | No. of PMMY Accounts | No. of SHGs Financed | Customer Complaints about Digital Transactions | Whether Providing SMS Banking | Whether Providing Internet/Mobile Banking | | Agatti | PSB1 | 3678 | 134 | 6 (Agri SHGs) | Nil | Yes | Yes | | Amini | PSB2 | 1021 | 175 | Nil | Majority of complaints are on failures occurred during digital financial transactions. | Yes | Yes | | Andrott | PSB3 | 1284 | 279 | Nil | Complaints about failure in digital financial transactions received twice in a week | Yes | Yes | | Chetlat | PSB4 | 105 | 38 | Nil | Two to three complaints from customers regarding failures in digital financial transactions | Yes | Yes | | Kadmat | PSB5 | 820 | 95 | 6 | Received two to five complaints regarding failure in digital transactions on a weekly basis | Yes | Yes | | Kalpeni | PSB6 | 178 | 92 | 2 | Received 10 to 15 complaints on a monthly basis regarding failure in making digital financial transactions owing to poor internet connectivity. | Yes | Yes | | Kavaratti | PSB7 | 4458 | 48 | 4 | Received one or two customer complaints regarding failure to do digital transactions on a monthly basis. | Yes | Yes | | Kavaratti | PSB8 | 1246 | 54 | Nil | Received two complaints regarding failure in digital financial transactions. | Yes | Yes | | Kiltan | PSB9 | 92 | 95 | Nil | Occasionally getting complaints from customers. | Yes | Yes | | Minicoy (Canara) | PSB10 | 2625 | 134 | Nil | Received 10 to 15 complaints. | Yes | Yes | | Minicoy | PSB11 | 112 | Nil | Nil | Occasionally getting complaints from customers | Yes | Yes | | Total | - | 14,335 | - | - | - | - | - | | Source: Discussion with bank officials in the selected 11 PSBs. |