7.1 The capital market fosters economic growth in various ways such as by augmenting the quantum of savings and capital formation and through efficient allocation of capital, which, in turn, raises the productivity of investment. It also enhances the efficiency of a financial system as diverse competitors viewith each other for financial resources. Further, it adds to the financial deepening of the economy by enlarging the financial sector and promoting the use of innovative, sophisticated and cost-effective financial instruments, which ultimately reduce the cost of capital. Well-functioning capital markets also impose discipline on firms to perform (Beck et al., 2000; Bandiera et al., 2000). Equity and debt markets can also diffuse stress on the banking sector by diversifying credit risk across the economy.

7.2 Although the capital market in India has a long history, during the most part, it remained on the periphery of the financial system. Various reforms undertaken since the early 1990s by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and the Government have brought about a significant structural transformation in the Indian capital market. As a result, the Indian equity market has become modern and transparent. However, its role in capital formation continues to be limited. The private corporate debt market is active mainly in the form of private placements, while the public issue market for corporate debt is yet to pick up. It is the primary equity and debt markets that link the issuers of securities and investors and provide resources for capital formation. In some advanced countries, especially the US, the new issue market has been quite successful in financing new companies and spurring the development of new technology companies. A growing economy requires risk capital and long-term resources in the form of debt for enabling the corporates to choose an appropriate mix of debt and equity. Long-term resources are also important for financing infrastructure projects. Therefore, in order to sustain India’s high growth path, the capital market needs to play a major role. The significance of a well-functioning domestic capital market has also increased as banks need to raise necessary capital from the market to sustain their growing operations.

7.3 This chapter is divided into four sections. Section I begins by discussing the role of the stock market in financing economic growth. This is followed by a brief overview of measures initiated to reform the capital market since the early 1990s. It then assesses the impact of various reform measures on the efficiency and stability parameters such as size, liquidity, transaction cost and volatility. The performance has been assessed against international best standards, wherever possible. In this section, a brief discussion is also presented on the stock prices and wealth effect from the point of view of its impact on aggregate demand. Section II discusses the need for developing the private corporate bond market for promoting growth and creating multiple financing channels. It presents the evolution of the debt market in India from the mid-1980s onwards, and various factors affecting its growth. It then presents experiences of other countries in developing the private corporate debt market. Section III suggests measures to enhance the role of the primary capital market in general and the private corporate debt market in particular. The last section sets out the concluding observations.

I. EQUITY MARKET

Role of the Stock Market in Financing Economic Growth

7.4 A growing body of empirical research shows that stock market development matters for growth as access to external capital allows financially constrained firms to expand. It is argued that countries with better-developed financial systems, especially those with liquid stock exchanges, tend to grow faster. On the other hand, Singh (1997) argues that stock market expansion is not a necessary natural progression of a country’s financial development and stock market development may not help in achieving quicker industrialisation and faster long-term economic growth in most of the developing countries because of several reasons. First, because of inherent volatility and arbitrariness of the stock market, the resulting pricing process is a poor guide to efficient investment allocation. Second, in the wake of unfavourable economic shocks, the interactions between the stock and currency markets may exacerbate macroeconomic instability and reduce long-term economic growth. Third, stock market development is likely to undermine the role of existing banking systems in developing countries, which have not been without merit in several countries, not least in highly successful East Asian economies.

7.5 A study on financial development and economic growth suggests that stock markets and financial intermediaries have grown hand-in-hand in the emerging market economies, which is popularly attributed to ‘complementarity hypothesis’. Some other studies also find that the levels of banking development and stock market liquidity exert a positive influence on economic growth. Levine and Zervos (1998) provide information on the independent impact of stock markets and banks on economic growth, capital accumulation and productivity in their cross-country study. They find that the initial level of stock market liquidity and the initial level of banking development are both positively and significantly correlated with future rates of economic growth, capital accumulation and productivity growth even after controlling for a few initial social, economic and political factors. These results do not lend much support to models that emphasise the tensions between bank-based and market-based systems as they suggest that stock markets provide different financial functions from those provided by banks. However, Levine and Zervos do not find that stock market size, measured by market capitalisation divided by GDP, is robustly correlated with growth. This implies that simply listing on a stock exchange does not necessarily foster resource allocation. Instead, it is the ability to trade ownership of the economy’s productive technologies that influences resource allocation and growth (Levine, 2003). Similar results were obtained by Beck and Levine (2003) by using panel techniques. Industry level studies have also found a positive relationship between financial development and growth (Rajan and Zingales, 1998), but an increase in financial development disproportionately boosts the growth of those companies that are naturally heavy users of external finance. Using firm-level data, Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic (1998) show that the proportion of firms that grow at rates exceeding the rate at which each firm can grow with only retained earnings and short-term borrowing is positively associated with stock market liquidity (and banking system size). Thus, there is ample literature supporting the role of financial development and the stock market in economic growth by easing external financing constraints.

7.6 Historically, different kinds of financial intermediaries have existed in the Indian financial system. Banks financed only working capital requirements of corporates. As the capital market was underdeveloped, a number of development finance institutions (DFIs) were set up at the all-India and the State levels to meet the long-term requirement of funds. As the stock market played a limited role in the early stages, the relationship between the stock market and the real economy in India has not been widely examined. Most of the earlier empirical studies focused on banks’ role in financial deepening and development. More recent work suggests that the functional relationship between stock market development and economic growth is weak in the Indian context (Nagaishi, 1999). On the contrary, Shah and Thomas (1997) argue that the stock market in India is more efficient than the banking system and hence an efficient capital market would contribute to long-term growth through efficient allocation and utilisation of resources. A revisit of this issue has found that both the banking sector and the stock market promote growth in the Indian economy and that they complement each other. However, the significance of the banking sector in economic development is much more important than the stock market, which has hitherto played only a limited role. The analysis found that economic growth also leads to stock market development. There is, thus, bi-directional relationship between stock market development and economic growth. These findings are, broadly, in sync with the ‘complementary hypothesis’ (Box VII.1).

Recent Developments in the Indian Equity Market

7.7 The Indian equity market has witnessed a series of reforms since the early 1990s. The reforms have been implemented in a gradual and sequential manner, based on international best practices, modified to suit the country’s needs. The reform measures were aimed at (i) creating growth-enabling institutions; (ii) boosting competitive conditions in the equity market through improved price discovery mechanism; (iii) putting in place an appropriate regulatory framework; (iv) reducing the transaction costs; and (v) reducing information asymmetry, thereby boosting the investor confidence. These measures were expected to increase the role of the equity market in resource mobilisation by enhancing the corporate sector’s access to large resources through a variety of marketable securities.

7.8 Institutional development was at the core of the reform process. The Securities and Exchange Board of India, which was initially set up in April 1988 as a non-statutory body, was given statutory powers in January 1992 for regulating the securities markets.

Box VII.1

Does Stock Market Promote Economic Growth in India?

In order to establish the relationship of various components of the financial sector, viz., banking sector and stock market, with economic growth in India, regression technique has been used. As the monthly GDP series is not available, seasonally adjusted monthly index of industrial production (IIP) was used as a proxy for economic activity. Before carrying out the regression analysis using ordinary least square (OLS), the monthly data were adjusted for seasonality and then the variables were log transformed. As an indicator of the capital market development, market capitalisation (MCAP) as a percentage of GDP, which measures the size of the market, and value traded ratio (VTR), which reflects the liquidity of the market, have been used. For the banking sector, bank credit (BCR) as a percentage of GDP has been taken as a measure of banking sector development. The period of the analysis was from April 1995 to June 2006.

It is found that both the stock market and the banking sector abet the level of economic activity in the country (equation 1). However, the relationship between stock market and economic activity is not strong as the coefficients of stock market activity, viz., MCAP and VTR, though significant, are very small. On the other hand, bank credit plays a very significant role. This confirms the bank-dominated financial system in India.

It is also found that both the banking sector and the economic growth promote stock market activity in India (equation 2).

References:

Shah, A., and Susan Thomas. 1997. “Securities Markets: Towards Greater Efficiency.” India Development Report, Oxford University Press.

Nagaishi, M. 1999. “Stock Market Development and Economic Growth: Dubious Relationship.” Economic and Political Weekly, July 17.

SEBI was given the twin mandate of protecting investors’ interests and ensuring the orderly development of the capital market.

7.9 The most significant reform in respect of the primary capital market was the introduction of free pricing. The Capital Issues (Control) Act, 1947 was repealed in 1992 paving the way for market forces in the determination of pricing of issues and allocation of resources for competing uses. The issuers of securities were allowed to raise capital from the market without requiring any consent from any authority for either making the issue or pricing it. Restrictions on rights and bonus issues were also removed. All companies are now able to price issues based on market conditions.

7.10 Without seeking to control the freedom of the issuers to enter the market and freely price their issues, the norms for public issues were made stringent in April 1996 to prevent fraudulent companies from accessing the market. Issuers of capital are now required to disclose information on various aspects such as track record of profitability, risk factors, etc. As a result, there has been an improvement in the standards of disclosure in the offer documents for the public and rights issues and easier accessibility of information to the investors. The improvement in disclosure standards has enhanced transparency, thereby improving the level of investor protection.

7.11 Issuers also have the option of raising resources through fixed price mechanism or the book building process. Book-building is a process by which demand for the securities proposed to be issued is built-up and the price for securities is assessed for determination of the quantum of such securities to be issued. Book building was introduced to improve the transparency in pricing of the scrips and determine proper market price for shares.

7.12 Trading infrastructure in the stock exchanges has been modernised by replacing the open outcry system with on-line screen based electronic trading. This has improved the liquidity in the Indian capital market and led to better price discovery. The trading and settlement cycles were initially shortened from 14 days to 7 days. Subsequently, to enhance the efficiency of the secondary market, rolling settlement was introduced on a T+5 basis. With effect from April 1, 2002, the settlement cycle for all listed securities was shortened to T+3 and further to T+2 from April 1, 2003. Shortening of settlement cycles helped in reducing risks associated with unsettled trades due to market fluctuations.

7.13 The setting up of the National Stock Exchange of India Ltd. (NSE) as an electronic trading platform set a benchmark of operating efficiency for other stock exchanges in the country. The establishment of National Securities Depository Ltd. (NSDL) in 1996 and Central Depository Services (India) Ltd. (CSDL) in 1999 has enabled paperless trading in the exchanges. This has also facilitated instantaneous electronic transfer of securities and eliminated the risks to the investors arising from bad deliveries in the market, delays in share transfer, fake and forged shares and loss of scrips. The electronic fund transfer (EFT) facility combined with dematerialisation of shares created a conducive environment for reducing the settlement cycle in stock markets.

7.14 The improvement in clearing and settlement system has brought a substantial reduction in transaction costs. Several measures were also undertaken to enhance the safety and integrity of the market. These include capital requirements, trading and exposure limits, daily margins comprising mark-to-market margins and VaR based margins. Trade/ settlement guarantee fund has also been set up to ensure smooth settlement of transactions in case of default by any member.

7.15 Trading in derivatives such as stock index futures, stock index options and futures and options in individual stocks was introduced to provide hedging options to the investors and to improve ‘price discovery’ mechanism in the market.

7.16 Another significant reform has been a move towards corporatisation and demutualisation of stock exchanges. Stock exchanges all over the world have been traditionally formed as ‘mutual’ organisations. The trading members not only provide broking services, but also own, control and manage such exchanges for their mutual benefit. In India, NSE was set up as a demutualised corporate body, where ownership, management and trading rights are in hands of three different sets of groups from its inception. The Stock Exchange, Mumbai, one of the two premier exchanges in the country, has since been corporatised and demutualised and renamed as the Bombay Stock Exchange Ltd. (BSE).

7.17 The stock exchanges have put in place a system for redressal of investor grievances for matters relating to trading members and companies. They ensure that critical and price-sensitive information reaching the exchange is made available to all classes of investor at the same point of time. Further, to protect the interests of investors, the Investor Protection Fund (IPF) has also been set up by the stock exchanges. The exchanges maintain an IPF to take care of investor claims, which may arise out of non-settlement of obligations by the trading member, who has been declared a defaulter, in respect of trades executed on the exchange. Measures of investor protection that have been put in place over the reform period have led to increased confidence among investors. The World Bank in its survey of ‘Doing Business’ has worked out an investor protection index, which measures the strength of minority shareholders against directors’ misuse of corporate assets for his/ her personal gain (World Bank, 2006). The index is the average of the disclosure index, director liability index, and shareholder suits index. The index ranges from 1 to 10, with higher values indicating better investor protection. Based on this index, India fares better than a large number of economies, including even some of the developed ones such as France and Germany (Chart VII.1).

7.18 Corporate Governance has emerged as an important tool for protection of shareholders. The corporate governance framework in India has evolved over a period of time since the setting up of the Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee by SEBI. According to the Economic Intelligence Unit Survey of 2003, corporate governance across the countries, India was rated the third best country to have good corporate governance code after Singapore and Hong Kong. India has a reasonably well-designed regulatory framework for the issuance and trading of securities, and disclosures by the issuers with strong focus on corporate governance standards.

7.19 To improve the availability of information to investors, all listed companies are required to publish unaudited financial results on a quarterly basis. To enhance the level of continuous disclosure by the listed companies, SEBI amended the listing agreement to incorporate segment reporting, related party disclosures, consolidated financial results and consolidated financial statements. The listing agreement between the stock exchanges and the companies has been strengthened from time to time to enhance corporate governance standards.

7.20 Another important development of the reform process was the opening up of mutual funds industry to the private sector in 1992, which earlier was the monopoly of the Unit Trust of India (UTI) and mutual funds set up by public sector financial institutions.

7.21 Since 1992, foreign institutional investors (FIIs) were permitted to invest in all types of securities, including corporate debt and government securities in stages and subject to limits. Further, the Indian corporate sector was allowed to access international capital markets through American Depository Receipts (ADRs), Global Depository Receipts (GDRs), Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds (FCCBs) and External Commercial Borrowings (ECBs). Eligible foreign companies have been permitted to raise money from domestic capital markets through issue of Indian Depository Receipts (IDRs).

7.22 Regulations governing substantial acquisition of shares and takeovers of companies have also been put in place. These are aimed at making the takeover process more transparent and to protect the interests of minority shareholders.

7.23 Besides strengthening the institutional design of the markets, the reforms have also brought about an increase in the number of service providers who add value to the market. The most significant development in this respect has been the setting up of credit rating agencies. By assigning ratings to debt instruments and by continuous monitoring and dissemination of the ratings, they help in improving the quality of information. At present, four credit rating agencies are operating in India. Besides, two other service providers, viz., registrars to issue and share transfer agents, have also grown in number, which help in spreading the services easily and at competitive prices.

7.24 The regulatory ambit has been widened in tune with the emerging needs and developments in the equity markets. Apart from stock exchanges, various intermediaries such as mutual funds, stock brokers and sub-brokers, merchant bankers, portfolio managers, registrars to an issue, share transfer agents, underwriters, debentures trustees, bankers to an issue, custodian of securities, venture capital funds and issuers have been brought under the SEBI’s regulatory purview.

Impact of Reforms on the Equity Market

7.25 The Indian equity market has witnessed a significant improvement, since the reform process began in the early 1990s, in terms of various parameters such as size of the market, liquidity, transparency, stability and efficiency. The changes in regulatory and governance framework have brought about an improvement in investor confidence.

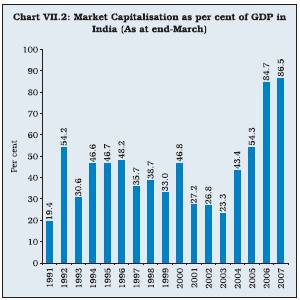

7.26 The most commonly used indicator of stock market development is the size of the market, measured by stock market capitalisation (the value of listed shares on the country’s exchanges) to GDP ratio. This ratio has improved significantly in India in recent years (Chart VII.2). Apart from new listings, the ratio may go up because of rise in stock prices. While during 1994-95 to 1999-00, 3,434 initial public offers (IPOs) amounting to Rs.37,626 crore were floated, during 2000-01 to 2005-06, 250 IPOs amounting to Rs.43,290 crore were floated. In 2006-07, 75 IPOs amounting to Rs.27,524 crore entered the market. The size of the market is influenced by several factors, including improvement in macroeconomic fundamentals, changes in financial technology and increase in institutional efficiency. A cross-country study has identified that in the case of India, the equity market size has expanded mostly because of change in financial technology, followed by change in macroeconomic fundamentals, while change in institutional efficiency had no impact on the market size (Li, 2007).

7.27 While the size of the Indian equity market still remains much smaller than many advanced economies such as the US, UK, Australia and Japan, it is significantly higher than many other emerging market economies, including Brazil and Mexico (Chart VII.3).

7.28 The turnover ratio (TOR), which equals the total value of shares traded on a country’s stock exchange divided by stock market capitalisation, is a commonly used measure of trading activity or liquidity in the stock markets. The turnover ratio measures trading relative to the size of the market. All things equal, therefore, differences in trading frictions will influence the turnover ratio. Another related variable is the value traded ratio (VTR), which equals the total value of domestic stocks traded on domestic exchanges as a share of GDP. This ratio measures trading relative to the size of the economy. Both TOR and VTR have improved significantly as compared to the early 1990s (Table 7.1). These ratios touched high levels between 1996-97 and 2000-01. This, however, largely reflected the impact of sharp rise in stock prices due to the IT boom. The price effect may lead to an increase in the liquidity ratios by boosting the value of stock transactions even without a rise in the number of transactions or a fall in transaction costs. Further, liquidity may be concentrated among larger stocks.

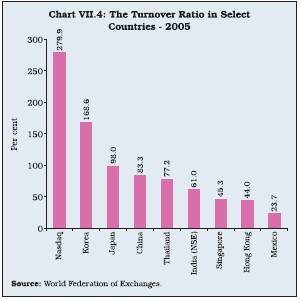

7.29 The turnover ratio exhibits substantial cross-country variations (Chart VII.4). The turnover ratio of NSE in 2005 was lower than that in NASDAQ, Korea, Japan, China and Thailand, but significantly higher than that of Singapore, Hong Kong, and Mexico stock exchanges. Automation of trading in stock exchanges has increased the number of trades and the number of shares traded per day, which, in turn, has helped in lowering transaction costs. The spread of trading terminals across the country has also aided in giving access to investors in the stock market. The opening of the Indian equity market to foreign institutional investors (FIIs) and growth in assets of mutual funds might have also contributed to the increased liquidity in the Indian stock exchanges.

Table 7.1: Liquidity in the Stock Market in India |

(Per cent) |

Year |

Turnover Ratio |

Value Traded Ratio |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1990-91 |

32.7 |

6.3 |

1991-92 |

20.3 |

11.0 |

1992-93 |

20.0 |

6.1 |

1993-94 |

21.1 |

9.8 |

1994-95 |

14.7 |

6.9 |

1995-96 |

20.5 |

9.9 |

1996-97 |

85.8 |

30.6 |

1997-98 |

98.0 |

38.0 |

1998-99 |

126.5 |

41.7 |

1999-00 |

167.0 |

78.1 |

2000-01 |

409.3 |

111.3 |

2001-02 |

134.0 |

36.0 |

2002-03 |

162.9 |

37.9 |

2003-04 |

133.4 |

57.9 |

2004-05 |

97.7 |

53.1 |

2005-06 |

78.9 |

66.9 |

2006-07 |

81.8 |

70.7 |

7.30 Apart from the frequency of trading, liquidity can also be measured by frictionless trading, proxied by the transaction cost. Transaction costs are of two types – direct and indirect. Direct costs arise from costs incurred while transacting a trade such as fees, commissions, taxes, etc. These costs are directly observable in the market. In addition, there are ‘indirect’ costs that are not directly observable but can be derived from the speed and efficiency of execution of trades. These can be captured by estimating ‘impact cost’ or cost of executing a transaction on a stock exchange, which varies with the size of the transaction. A liquid market is one where transaction costs (indirect) are low. The impact cost for purchase or sale of Rs.50 lakh of the Nifty portfolio dropped steadily and sharply from a level of 0.12 per cent in 2002 to 0.08 per cent in 2006, while in the case of purchase or sale of Rs.25 lakh of the Nifty Junior portfolio, the impact cost dropped from a level of 0.41 per cent in 2002 to 0.16 per cent in 2006 (Chart VII.5). Besides, even in terms of direct costs that the participants have to pay as fee to the broker and the exchange, and the securities transaction tax, the charges in India are among the lowest in the world (Government of India, 2005-06). As per the SEBI-NCAER Survey of Indian Investors, 2003, there has been a substantial reduction in transaction cost in the Indian securities market, which declined from a level of more than 4.75 per cent in 1994 to 0.60 per cent in 1999, close to the global best level of 0.45 per cent. Further, the Indian equity market had the third lowest transaction cost after the US and Hong Kong. As compared with some of the developed and emerging markets, transaction costs for institutional investors on the Indian stock exchanges are also one of the lowest.

7.31 In all developed markets, stock markets provide mechanisms for hedging. Derivatives have increasingly gained popularity as instruments of risk management. By locking-in asset prices, derivative products enable market participants to partially or fully transfer price risks. Equity derivatives were introduced in India in 2000. Since then, India has been able to build a modern and transparent derivatives market in a relatively short period of time. The turnover in derivative market has also risen sharply, though a large part of the trading is concentrated in single stock futures (Chart VII.6). In several other countries, it is index futures and options, which are the most popular derivative products. The number of stocks on which individual stock derivatives are traded has gone up steadily from 31 in 2001 to 117 at present, which has helped in percolating liquidity and market efficiency down to a wide range of stocks.

7.32 According to the World Federation of Stock Exchanges, NSE was the leader in the trading of single stock futures in 2006, while in the trading of index futures, NSE was at the fourth position (Table 7.2).

Table 7.2: Top Five Equity Derivative |

Exchanges in the world - 2006 |

A. Single Stock Futures Contracts |

Exchange |

No. of contracts |

Rank |

National Stock Exchange, India |

100,430,505 |

1 |

Jakarta Stock Exchange, Indonesia |

69,663,332 |

2 |

Eurex |

35,589,089 |

3 |

Euronext.liffe |

29,515,726 |

4 |

BME Spanish Exchange |

21,120,621 |

5 |

B. Stock Index Futures Contracts |

|

|

Exchange |

No. of contracts |

Rank |

Chicago Mercantile Exchange |

470,180,198 |

1 |

Eurex |

270,134,951 |

2 |

Euronext.liffe |

72,135,006 |

3 |

National Stock Exchange, India |

70,286,258 |

4 |

Korea Stock Exchange |

46,562,881 |

5 |

Source : World Federation of Exchanges. |

|

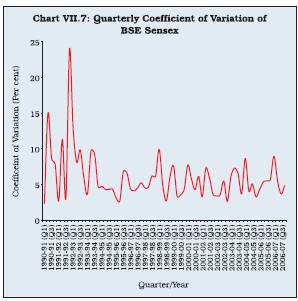

7.33 The Indian stock markets have also become less volatile due to the strengthening of the market design. This is reflected in sharp decline in the volatility in stock prices (Chart VII.7). The robustness of the risk management practices at the stock exchange level was also evident as the exchanges were able to contain the impact of volatile movement in stock prices on May 17, 2004 and May 22, 2006 without any disruption in financial markets.

7.34 The Indian equity market, however, has been somewhat more volatile as compared with some other markets such as the US, Singapore and Malaysia (Table 7.3).

7.35 Significant improvement has also taken place in clearing and settlement mechanism in India. Out of a score of 100, the settlement benchmark, which

Table 7.3: Volatility in Select World Stock Markets |

Year |

US |

UK |

Hong Kong |

Singapore |

Malaysia |

Brazil |

Mexico |

Japan |

India |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

1992 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

7.0 |

1.6 |

– |

3.3 |

1993 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

1.4 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

3.4 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

1994 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.9 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

3.9 |

1.8 |

0.9 |

1.4 |

1995 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

3.4 |

2.3 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1996 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

1997 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

2.5 |

1.5 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

1.8 |

0.4 |

1.6 |

1998 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

2.3 |

1.4 |

1.9 |

1999 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.8 |

2.9 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

2000 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

2.0 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

1.4 |

2.2 |

2001 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

2002 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

2003 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

0.7 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

2004 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

1.8 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

2005 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

1.6 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

Source : Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Securities Market, 2006, SEBI. |

provides a means of tracking the evolution of settlement performance over a period of time, improved from 8.3 in 1994 to 93.1 in 2004. The safekeeping benchmark, which provides the efficiency of a market in terms of collection of dividend and interest, protection of rights in the event of a corporate action, improved from 71.8 in 1994 to 91.8 in 2004. The operational risk benchmark that takes into consideration the settlement and safekeeping benchmarks and other operational factors such as the level of compliance with G30 recommendations, the complexity and effectiveness of the regulatory and legal structure of the market, and counterparty risk, improved from 28.0 out of 100 in 1994 to 67.2 in 2004 (NSE, 2005).

7.36 Despite significant improvement in trading and settlement infrastructure, risk management system, liquidity and containment of volatility, the role of the Indian capital market (equity and debt) has remained less significant as is reflected in the savings in the form of capital market instruments and resources raised by the corporates. Savings of the household sector in the form of shares and debentures and units of mutual funds have remained at a low level, barring the period from 1990-91 to 1994-95, when they were relatively high. It is also significant to note that the share of savings in capital market instruments (shares, debentures and units of mutual funds) during 2000-01 to 2005-06 was lower than that in the 1980s and 1990s (Table 7.4).

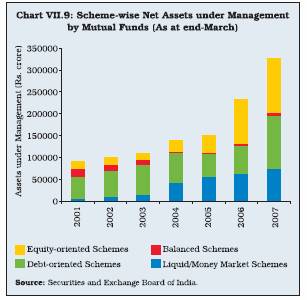

7.37 The opening up of the mutual funds sector to the private sector brought about an element of competition. The mutual fund industry recovered from the adverse impact of the UTI imbroglio and has begun to attract substantial funds. The growing popularity of mutual funds is clearly evident from the increase in net funds mobilised (net of redemptions) by them (Chart VII.8). The buoyancy in stock markets during last two years enabled mutual funds to attract fresh inflow of funds. Although the share of equity-oriented schemes increased significantly in recent years, most of the funds mobilised by mutual funds were through liquid/money market schemes, which remain attractive for parking of funds by large investors with a short-term perspective.

Table 7.4: Share of Various Instruments in Gross Financial Savings of the Household Sector in India |

(Per cent) |

Period |

Currency |

Bank and |

Insurance, PF, |

Units of |

Claims on |

Shares and |

|

|

non-bank deposits |

Trade debt |

UTI |

Government |

Debentures@ |

1970-71 to 1979-80 |

13.9 |

48.6 |

31.3 |

0.5 |

4.2 |

1.5 |

1980-81 to 1989-90 |

11.9 |

45.0 |

25.9 |

2.2 |

11.1 |

3.9 |

1990-91 to 1994-95 |

10.8 |

39.6 |

25.5 |

6.6 |

8.1 |

9.4 |

1995-96 to 1999-00 |

9.7 |

43.4 |

30.5 |

0.9 |

10.8 |

4.7 |

2000-01 to 2005-06 |

8.9 |

40.9 |

29.0 |

-0.8 |

18.8 |

3.2 |

@ : Includes investment in shares and debentures of credit/non-credit societies,

public sector bonds and investment in mutual funds (other than UTI).

Note : Gross financial savings data for the year 2004-05 are on new base, i.e., 1999-2000.

Source : Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, 2005-06, RBI. |

7.38 As a result of large mobilisation of funds and robust stock markets, the assets under management of mutual funds increased sharply during last two years (Chart VII.9).

7.39 Despite significant fund mobilisation in the recent years, the penetration of the mutual funds industry in India remains fairly low as compared with even some of the emerging market economies (Chart VII.10).

Table 7.4: Share of Various Instruments in Gross Financial Savings of the

Household Sector in India |

(Per cent) |

Period |

Currency |

Bank and |

Insurance, PF, |

Units of |

Claims on |

Shares and |

|

|

non-bank deposits |

Trade debt |

UTI |

Government |

Debentures@ |

1970-71 to 1979-80 |

13.9 |

48.6 |

31.3 |

0.5 |

4.2 |

1.5 |

1980-81 to 1989-90 |

11.9 |

45.0 |

25.9 |

2.2 |

11.1 |

3.9 |

1990-91 to 1994-95 |

10.8 |

39.6 |

25.5 |

6.6 |

8.1 |

9.4 |

1995-96 to 1999-00 |

9.7 |

43.4 |

30.5 |

0.9 |

10.8 |

4.7 |

2000-01 to 2005-06 |

8.9 |

40.9 |

29.0 |

-0.8 |

18.8 |

3.2 |

@ : Includes investment in shares and debentures of credit/non-credit societies,

public sector bonds and investment in mutual funds (other than UTI).

Note : Gross financial savings data for the year 2004-05 are on new base, i.e., 1999-2000.

Source : Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, 2005-06, RBI. |

7.40 Resource mobilisation from the primary capital market by way of public issues, which touched the peak during 1994-95, declined in subsequent years (Chart VII.11). Although resource mobilisation picked up during the period from 2003-04 to 2005-06, resource mobilisation as per cent of GDP and gross domestic capital formation (GDCF) in 2005-06 was lower than that in 1990-91 (Chart VII.12). This was despite the fact that the industrial sector has remained buoyant for the last 3 years and has witnessed large capacity additions.

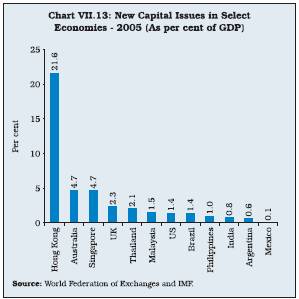

7.41 The size of the primary market in India remains much smaller than many advanced economies such as Hong Kong, Australia, the UK, the US and Singapore, as also emerging market economies such as Thailand, Malaysia, Brazil and the Philippines (Chart VII.13).

7.42 The relative decline in the public issues segment could be attributed to four main factors:

(i) tightening of entry and disclosure norms;

(ii) increased reliance by corporates on internal generation of funds;

(iii) corporates raising resources from the international capital markets; and

(iv) emergence of the private placement market.

7.43 In the early 1990s, the liberalisation of the industrial sector and free pricing of capital issues led to an increased number of companies tapping the primary capital market to mobilise resources. Several corporates charged a high premium not justified by their fundamentals. Also, several companies vanished after raising resources from the capital market. SEBI, therefore, strengthened the norms for public issues while retaining the freedom of the issuers to enter the new issues market and to freely price their issues. The disclosure standards were also strengthened for companies coming out with public issues for improving the levels of investor protection. Strict disclosure norms and entry point restrictions prescribed by SEBI made it difficult for most new companies without an established track record to access the public issues market. Whereas this helped to improve the quality of paper coming into the market, it contributed to a decline in the number of issues and the amount mobilised from the market. This period also coincided with slackening of investment activity across various sectors. In particular, the pace of private investment originating from the private corporate sector lost momentum in the second half of the 1990s on account of factors such as reduced savings from this sector and lack of public investment in infrastructure. The dampening of investment climate also resulted in a drastic fall in the number of companies accessing the primary capital market for funds. The slowdown in activity in the primary market could also be attributed to the subdued conditions in the secondary market.

7.44 During the second half of the 1990s and thereafter, the pattern of financing of investments by the Indian corporate sector also underwent a significant change. Corporates came to rely heavily on internal sources of funds, constituting 60.7 per cent of total funds during 2000-01 to 2004-05 as against 29.9 per cent during 1990-91 to 1994-95. Among external sources, however, while share of equity capital, borrowings by way of debentures and from FIs declined sharply, that of borrowings from banks increased significantly (Table 7.5).

7.45 Indian corporates were allowed to raise funds from the international capital markets by way of ADRs/ GDRs, FCCBs and external commercial borrowings in the early 1990s. This widened the financing choices available to corporates, enabling them to raise large resources from the international capital markets, especially in the recent period (Chart VII.14).

Table 7.5: Pattern of Sources of Funds for |

Indian Corporates |

(Per cent to total) |

Item |

1985-86 |

1990-91 |

1995-96 |

2000-01 |

to |

to |

to |

to |

1989-90 |

1994-95 |

1999-2000 |

2004-05 |

1. |

Internal Sources |

31.9 |

29.9 |

37.1 |

60.7 |

2. |

External Sources |

68.1 |

70.1 |

62.9 |

39.3 |

|

of which: |

|

|

|

|

|

a) Equity capital |

7.2 |

18.8 |

13.0 |

9.9 |

|

b) Borrowings |

37.9 |

32.7 |

35.9 |

11.5 |

|

of which: |

|

|

|

|

|

(i) Debentures |

11.0 |

7.1 |

5.6 |

-1.3 |

|

(ii) From Banks |

13.6 |

8.2 |

12.3 |

18.4 |

|

(iii) From FIs |

8.7 |

10.3 |

9.0 |

-1.8 |

|

c) Trade dues & other |

22.8 |

18.4 |

13.7 |

17.3 |

|

current liabilities |

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Memo: |

|

|

|

|

(i) |

Share of Capital Market |

18.2 |

26.0 |

18.6 |

8.6 |

|

Related Instruments |

|

|

|

|

|

(Debentures and Equity |

|

|

|

|

|

Capital) |

|

|

|

|

(ii) |

Share of Financial |

22.2 |

18.3 |

21.3 |

16.6 |

|

Intermediaries |

|

|

|

|

|

(Borrowings from |

|

|

|

|

|

Banks and FIs) |

|

|

|

|

(iii) |

Debt-Equity Ratio |

88.4 |

85.5 |

65.2 |

61.6 |

Note : Data pertain to a sample of non-government non-financial

public limited companies.

Source : Article on “Finances of Public Limited Companies”, RBI Bulletin

(various issues). |

7.46 International equity issuances by Indian companies increased sharply between 2000 and 2005 and were significantly higher than those by corporates in several other emerging markets (Chart VII.15).

7.47 The private placement market also emerged in the mid-1990s. The convenience and flexibility of issuance made this segment attractive for companies. Mid-sized companies wishing to issue long-term debt securities at fixed rates of interest preferred the private placement market. Some of these companies might be new entrants in the market, which would not have been able to float public issues in the absence of a track record of past performance. However, at times, even large-sized companies also prefer to issue securities in the private placement market. A major advantage of private placement is tailor-made deals, which suit the requirements of both the parties. Many companies may also prefer private placements if they wish to raise funds quickly. The resources raised through the private placement market, which amounted to Rs.13,361 crore in 1995-96, increased to Rs.96,369 crore in 2005-06 (as detailed in section III). Currently, the size of the private placement market is estimated to be more than three times of the public issues market (Chart VII.16). Although the private placement market is cost-effective and less time-consuming, it lacks transparency. It also deprives retail investor from participating in the capital market.

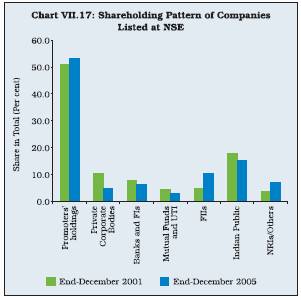

7.48 The available data on the shareholding pattern in India between 2001 and 2005 suggest that promoters continue to hold a large portion in the equity of the companies. In fact, the share of promoters increased marginally over the period. The share of equity held by FIIs/NRIs also increased. On the other hand, the share of equity held by mutual funds, banks/FIs and Indian public declined (Chart VII.17). Concentrated ownership prevents the broad distribution of gains from the equity market development. Concentration of ownership among promoters and corporate bodies (through cross-holdings) also has implications for the functioning of the corporate governance framework and protection of rights of minority shareholders.

7.49 To sum up, the Indian capital market has become modern in terms of market infrastructure and trading and settlement practices. The capital market has also become a much safer place than it was before the reform process began. The secondary capital market in India has also become deep and liquid. There has also been a reduction in transaction costs and significant improvement in efficiency and transparency. However, the role of the domestic capital market in capital formation in the country, both directly and indirectly through mutual funds, continues to be less significant. The public issues segment of the capital market, in particular, has remained small. Rather, it has shrunk over the last 15 years.

Asset Prices and Wealth Effect

7.50 Apart from playing a vital role in the growth process through mobilisation of resources and improved allocative efficiency, the stock market also promotes economic growth indirectly through its effect on consumption and hence aggregate demand. In recent years, financial balance sheets of economic agents have deepened on account of increase in financial assets and liabilities relative to income and an increase in the holding of assets whose returns are directly linked to the market. Market-linked assets in the form of real estate and equities have become important arguments in the wealth function of households and firms. The tendency of a greater share of wealth to be held in market-linked assets has increased the sensitivity of spending decisions. Price movements in these assets, therefore, may lead more directly to changes in consumption with attendant implications for monetary policy.

7.51 Empirical studies have shown that large price changes may have substantial wealth effects on consumption and savings. Ludwig and Slok (2002) estimated panel data from 16 OECD countries and concluded that there is a significant long run impact of stock market wealth on private consumption. They have singled out five channels of transmission from changes in stock market wealth to changes in consumption. One, if the value of consumers’ stock holding increases and consumers realise their gains, then consumption will increase. This is known as realised wealth effect. Two, increase in stock prices can also have an expectations effect where the value of stocks in pension accounts and other locked-in accounts increases. The consumers may not realise these gains but they result in higher present consumption on expectation that income and wealth will be higher in future. This is termed as unrealised wealth effect. Three, increase in stock market prices increases the value of investor portfolio. Borrowing against the value of this portfolio, in turn, allows the consumer to increase consumption. This is called liquidity constraints effect. Four, an increase in stock prices may lead to higher consumption for stock option owners as a result of increase in value of stock options. This increase may be independent of whether the gains have been realised or unrealised. This is termed as stock option value effect. Five, consumption of households, who do not participate in the stock market, may be indirectly affected by changes in stock market prices. Asset prices contain information about future movements in real variables (Christoffersen and Slok, 2000). Hence, a decline in stock prices leads to increased uncertainty about future income, i.e., decrease in consumer confidence and, therefore, decline in durable consumption (Romer, 1990). This is an indirect effect.

7.52 The impact of changes in stock prices on consumption was found to be bigger in economies with market-based financial systems than in economies with bank-based financial systems. Further, this impact from stock markets to consumption has increased over time for both sets of countries. While the effect of housing prices on consumption is ambiguous, the wealth effect has become more important over time.

7.53 Effect of stock prices on consumption appears to be strongest in the US, where most estimates point to an elasticity of consumption spending relative to net stock market wealth in the range of 0.03 to 0.07. In contrast, studies have not found any significant impact of stock prices on private consumption in France and Italy. In Canada, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, the effects are significant but smaller than in the United States. This is reflective of the smaller share of stock ownership relative to other financial assets in these countries, as well as more concentrated distribution of stock ownership across households in continental Europe as compared with the US. The effect of changes in real property prices on consumption was found to be much stronger in European Union countries. Rising real property prices can affect consumption not only through higher realised home values but also by the households’ ability to refinance a mortgage or go for reverse mortgages (IMF, 2000). However, in the Indian context, the wealth effect is limited as the household sector holds a very small share of its savings in stocks, i.e., about 5 per cent in 2005-06. As households diversify their portfolios in equities, the asset price channel of monetary transmission could strengthen as wealth effect becomes more important.

II. PRIVATE CORPORATE DEBT MARKET

7.54 The private corporate debt market provides an alternative means of long-term resources (alternative to financing by banks and financial institutions) to corporates. The size and growth of private corporate debt market depends upon several factors, including financing patterns of companies. Among market-based sources of financing, while the equity markets have been largely developed, the corporate bond markets in most emerging market economies (EMEs) have remained relatively underdeveloped. This has been the result of dominance of the banking system combined with the weaknesses in market infrastructure and inherent complexities. However, credit squeeze following the Asian financial crisis in the mid-1990s drew attention of policy makers to the importance of multiple financing channels in an economy. Alternative sources of finance, apart from banks, need to be actively developed to support higher levels of investment and economic growth. The development of corporate debt market has, therefore, become the prime concern of regulators in developing countries.

7.55 As in several other EMEs, corporates in India have traditionally relied heavily on borrowings from banks and financial institutions (FIs) to finance their investments. Equity financing was also used, but largely during periods of surging equity prices. However, bond issuances by companies have remained limited in size and scope. Given the huge funding requirements, especially for long-term infrastructure projects, the private corporate debt market has a crucial role to play and needs to be nurtured.

Significance of the Corporate Debt Market

7.56 In any country, companies face different types of financing choices at different stages of development. Reflecting the varied supplies of different types of capital and their costs, regulatory policies and financial innovations, the financing patterns of firms vary geographically and temporally. Some studies have observed that while developed countries rely more on market-based sources of finance, the developing countries rely more on bank-based sources. The development of a corporate bond market, for direct financing of the capital requirements of corporates by investors assumes paramount importance, particularly in a liberalised financial system (Sakakibara, 2001). From the perspective of developing countries, a liquid corporate bond market can play a critical role in supporting economic development as it supplements the banking system to meet the requirements of the corporate sector for long-term capital investment and asset creation. It provides a stable source of finance when the equity market is volatile. Further, with the decline in the role of specialised financial institutions, there is an increasing realisation of the need for a well-developed corporate debt market as an alternative source of finance. Corporate bond markets can also help firms reduce their overall cost of capital by allowing them to tailor their asset and liability profiles to reduce the risk of maturity and currency mismatches. A private corporate bond market is important for nurturing a credit culture and market discipline. The existence of a well-functioning bond market can lead to the efficient pricing of credit risk as expectations of all bond market participants are incorporated into bond prices.

7.57 In many Asian economies, banks have traditionally been performing the role of financial intermediation. The East Asian crisis of 1997 underscored the limitations of weak banking systems. The primary role of a banking system is to create and maintain liquidity that is needed to finance production within a short-term horizon. The crisis showed that over-reliance on bank lending for debt financing exposes an economy to the risk of a failure of the banking system. Banking systems, therefore, cannot be the sole source of long-term investment capital without making an economy vulnerable to external shocks. In times of financial distress, when banking sector becomes vulnerable, the corporate bond markets act as a buffer and reduce macroeconomic vulnerability to shocks and systemic risk through diversification of credit and investment risks. By contributing to a more diverse financial system, a bond market can promote financial stability. A bond market may also help the banking system in difficult conditions by allowing banks to recapitalise their balance sheets through securitisation (IOSCO, 2002).

7.58 The available economic literature suggests that meeting the demand for long-term funds by corporates, especially in developing economies requires multiple financing channels such as the equity market, the debt market, banks and other financial institutions. Indirect financing by banks and direct financing by bonds also improve firms’ capital structures. From a broader sense of macroeconomic stability and growth, the complementary nature of bank financing and direct financing by the market in financing corporates is desirable. It has been established that they indeed play a complementary role in the emerging market economies (Takagi, 2001).

7.59 Apart from providing a channel for financing investments, the corporate bond markets also contribute towards portfolio diversification for holders of long-term funds. Effective asset management requires a balance of asset alternatives. In view of the underdeveloped state of the corporate bond markets, there would be an overweight position in government securities and even equities. The existence of a well-functioning corporate bond market widens the array of asset choices for long-term investors such as pension funds and insurance companies and allows them to better manage the maturity structure of their balance sheets.

7.60 The financial structure of corporates has implications for monetary policy. Bond markets give an assessment of expected interest rates through the term structure of interest rates. The shape of the yield curve provides useful information about market expectations of future interest rates and inflation rates. Bond derivatives can also provide important information about the prevailing uncertainty about future interest rates. Such information gives important clues on whether market expectations deviate too far from central banks’ own evaluation of the current circumstances. In other words, bond markets can provide relevant information about risks to price stability. In situations when banks may adopt an oligopolistic pricing behaviour, the dynamic response of monetary policy changes works mainly through the bond market. Further, when the banking sector is impaired, as in Thailand in 1997, a change in policy interest rate can still have some effect through the change in behaviour and issuing costs for corporate bonds.

State of the Corporate Debt Market in India

7.61 In India, banks and FIs have traditionally been the most important external sources of finance for the corporate sector. India has traditionally been a predominantly bank-based system. This picture is generally characteristic of most Asian economies. The second half of the 1980s saw some activity in primary bond issuances, but these were largely by the PSUs. The period of ‘debenture boom’ in the late 1980s, however, proved to be short-lived. The corporates relied more on banks for meeting short-term working capital requirements and DFIs for financing long-term investment. However, with the conversion of two large DFIs into banks, a gap has appeared for long-term finance. Commercial banks have managed to fill this gap, but only to an extent as there are asset-liability mismatch issues for banks in providing longer-maturity credit. The problems associated with the diminishing role of DFIs appeared less severe as this period coincided with a decline in the reliance of the corporates on external financing. However, this situation may change in future.

7.62 In the 1990s, the equity market in India witnessed a series of reforms, which helped in bringing it on par with international standards. However, the corporate debt market has not been able to develop due to lack of market infrastructure and a comprehensive regulatory framework. For a variety of reasons, the issuers resorted to ‘private placement’ of bonds as opposed to ‘public issues’ of bonds. The issuances of bonds to the public have declined sharply since the early 1990s. From an annual average of Rs.7,513 crore raised by way of public debt issues during 1990-95, the mobilisation fell to Rs.5,526 crore during 1995-2000 and further to Rs.4,433 crore during 2000-05 (Chart VII.18). The decline is expected to be much

sharper in real terms, i.e., adjusted for rise in inflation. In contrast, the mobilisation of funds by private placement of debt increased sharply from an average of Rs.33,638 crore during 1995-2000 to Rs.69,928 crore during 2000-05. In 2005-06, the mobilisation of funds by public issue of debt shrank to a measly sum of Rs.245 crore, while the resources raised by way of private placement of debt swelled to Rs.96,369 crore. The share of resources raised by private placements in total debt issues correspondingly increased from 69.1 per cent in 1995-96 to 99.8 per cent in 2005-06. This trend continued in 2006-07.

7.63 The emergence of private placement market has provided an easier alternative to the corporates to raise funds (Box VII.2). Although the private placement market provides a cost effective and time saving mechanism for raising resources, the unbridled growth of this market has raised some concerns. The quality of issues and extent of transparency in the private placement deals remain areas of concern even though privately placed issues by listed companies are now required to be listed and also subject to necessary disclosures. In the case of public issues, all the issues coming to the market are screened for their quality and the investors rely on ratings and other public information for evaluation of risk. Such a screening mechanism is missing in the case of private placements. This increases the risk associated with

Box VII.2

Private Placement Market in India

In private placement, resources are raised privately through arrangers (merchant banking intermediaries) who place securities with a limited number of investors such as financial institutions, corporates and high net worth individuals. Under Section 81 of the Companies Act, 1956, a private placement is defined as ‘an issue of shares or of convertible securities by a company to a select group of persons’. An offer of securities to more than 50 persons is deemed to be a public issue under the Act.

Corporates access the private placement market because of its certain inherent advantages. First, it is a cost and time-effective method of raising funds. Second, it can be structured to meet the needs of the entrepreneurs. Third, private placement does not require detailed compliance of formalities as required in public or rights issues. The private placement market was not regulated until May 2004. In view of the mushrooming growth of the market and the risk posed by it, SEBI prescribed that the listing of all debt securities, irrespective of the mode of issuance, i.e., whether issued on a private placement basis or through public/rights issue, shall be done through a separate listing agreement. The Reserve Bank also issued guidelines to the financial intermediaries under its purview on investments in non-SLR securities including, private

placement. In June 2001, boards of banks were advised to lay down policy and prudential limits on investments in bonds and debentures, including cap on unrated issues and on a private placement basis. The policy laid down by banks should prescribe stringent appraisal of issues, especially by non-borrower customers, provide for an internal system of rating, stipulate entry-level minimum ratings/quality standards and put in place proper risk management systems.

The private placement market in India, which shot into prominence in the early 1990s, has grown sharply in recent years. The resource mobilisation by way of private placements increased from Rs.13,361 crore in 1995-96 to Rs.96,369 crore in 2005-06, recording an average annual growth of over 25 per cent during the decade (Chart A). The private placement market remained largely confined to financial companies and central PSUs and state-level undertakings. These institutions together accounted for over 75 per cent share in resource mobilisation by private placements. The resources raised by non-government non-financial companies remained comparatively insignificant (Chart B). Most of the resources from the market are raised by way of debt, with a majority of issues carrying ‘AAA’ or ‘AA’ rating.

privately placed securities. Further, the private placement market appears to be growing at the expense of the public issues market, which has some distinct advantages in the form of wider participation by the investors and, thus, diversification of the risk.

7.64 The size of the Indian corporate debt market is very small in comparison with not only developed markets, but also some of the emerging market economies in Asia such as Malaysia, Thailand and China (Table 7.6).

7.65 In view of the dominance of the private placement segment, most of the corporate debt issues in India do not find a way into the secondary market due to limited transparency in both primary and secondary markets. Liquidity is also constrained on account of small size of issues. For instance, the average size of issue of privately placed bonds in 2005-06 worked out to around Rs.90 crore, less than half of an average size of an equity issue. Out of nearly 1,000 bond issues in the private placement market, only around 3 per cent of the issues were of the size of more than Rs.500 crore. Some companies entered the market more than 100 times in a single year to raise funds through small tranches. As a result, the secondary market for corporate debt is characterised by poor liquidity and trading is confined largely to the top 5 or 10 bond papers (Bose and Coondoo, 2003). The government bond market has become reasonably liquid, while the trading in private corporate debt

Table 7.6: Size of Domestic Corporate Debt Market |

and other Sources of Local Currency Funding |

(As at end-2004) |

(As per cent of GDP) |

Country |

Corporate bonds

outstanding |

Government bonds

outstanding |

Domestic

credit |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

US |

128.8 |

42.5 |

89.0 |

Korea |

49.3 |

23.7 |

104.2 |

Japan |

41.7 |

117.2 |

146.9 |

Malaysia |

38.8 |

36.1 |

113.9 |

Hong Kong |

35.8 |

5.0 |

148.9 |

New Zealand |

27.8 |

19.9 |

245.5 |

Australia |

27.1 |

13.8 |

185.4 |

Singapore |

18.6 |

27.6 |

70.1 |

Thailand |

18.3 |

18.5 |

84.9 |

China |

10.6 |

18.0 |

154.4 |

India |

3.3 |

29.9 |

60.2 |

Indonesia |

2.4 |

15.2 |

42.6 |

Philippines |

0.2 |

21.8 |

49.8 |

Source : Bank for International Settlements, 2006. |

securities has remained insignificant (Table 7.7). Typically, the turnover ratios differ widely for government and corporate debt securities across the world. The turnover ratios for Asian corporate bond markets are a small fraction of those for government bond markets reflecting low levels of liquidity. Liquidity differences for government and corporate bond markets are expected because corporate debt issues are more heterogeneous and smaller in size than government bond issues. Even in the US, the turnover ratio for corporate bonds was less than 2 per cent in 2004 as compared with turnover ratio of more than 30 per cent for government bonds (BIS, 2006).

7.66 Development of the domestic corporate debt market in India is constrained by a number of factors - low issuance leading to illiquidity in the secondary market, narrow investor base, inadequate credit assessment skills, high costs of issuance, lack of transparency in trades, non-standardised instruments, comprehensive regulatory framework and underdevelopment of securitisation products. The market suffers from deficiencies in products, participants and institutional framework. This is despite the fact that India is fairly well placed insofar as pre-requisites for the development of the corporate bond market are concerned (Mohan, 2004b). There is a reasonably well-developed government securities market, which generally precedes the development of the market for corporate debt securities. The major stock exchanges have trading platforms for the transactions in debt securities. The infrastructure also exists for clearing and settlement. The Clearing Corporation of India Limited (CCIL) has been successfully settling trades in government bonds, foreign exchange and other money market instruments. The experience with the depository system has been satisfactory. The presence of multiple rating agencies meets the requirement of an assessment framework for bond quality.

Table 7.7: Turnover of Debt Securities |

(Rs. crore) |

Year |

Government Bonds* |

Corporate Bonds |

2000-01 |

5,72,145 |

14,486 |

2001-02 |

12,11,945 |

19,586 |

2002-03 |

13,78,158 |

35,876 |

2003-04 |

16,83,711 |

41,760 |

2004-05 |

11,60,632 |

37,312 |

2005-06 |

8,81,652 |

24,602 |

2006-07 (April-Feb.) |

9,71,414 |

12,099 |

*: Outright transactions in government securities.

Source : RBI; National Stock Exchange of India Limited. |

7.67 With the intent of the development of the corporate bond market along sound lines, some initiatives were taken by the SEBI in the past few years. These measures largely aimed at improving disclosures in respect of privately placed debt issues. In view of the immediate need to design a suitable framework for the corporate debt market, it was announced in the Union Budget 2005-06 that a High Level Expert Committee on Corporate Bonds and Securitisation would be set up to look into the legal, regulatory, tax and mortgage design issues for the development of the corporate bond market. The High Level Committee (Chairman: Dr. R. H. Patil), which submitted its report in December 2005, looked into the factors inhibiting the development of an active corporate debt market in India and made several suggestions for developing the market infrastructure for development of primary as well as secondary corporate bond market (Box VII.3).

7.68 At the current time, when India is endeavoring to sustain its high growth rate, it is necessary that financing constraints in any form are removed and alternative financing channels are developed in a systematic manner for supplementing traditional bank credit. The problem of ‘missing’ corporate bond market, however, is not unique to India alone. Predominantly bank-dominated financial systems in most Asian economies faced this situation. Many Asian economies woke up to meet this challenge in the wake of the Asian financial crisis. During less than a decade, the domestic bond markets of many Asian economies have undergone significant transformation. In the case of India, however, the small size of the private corporate debt market has shrunk further. This trend needs to be reversed soon. India could learn from the experiences of countries that have undertaken the process of reforming their domestic corporate bond markets.

Lessons from Experiences of other Countries

7.69 The corporate bond markets have developed at a different pace in different countries across the globe. While the local environment shaped the developments in a major way in most economies, there were certain common elements of reform that aimed at removing various bottlenecks impeding the growth of this segment. It is difficult to find much uniformity in the various features of the corporate bond market across the countries. This is partly because of the complex nature of bond contracts and variations in market practices across countries. The size of the corporate bond market also differs widely across the countries, with the US and Japan having large markets, followed by Korea, China and Australia (refer to Table 7.6). Corporates would have limited incentive to tap bond markets when banks are willing to lend at low spreads. Even among developed economies, the dominance of the banking sector in Europe and correspondingly small size of the corporate bond market is in sharp contrast to the US where corporate debt market plays a bigger role in corporate financing than banks. The European bond markets have, however, grown in size after the introduction of euro in 1999. The US is perhaps the only country with a bigger market for corporate bonds as compared with domestic credit market. The size of the US corporate bond market is almost as big as its equity market. While the corporate bond market in the US has existed for a long time, Canada, Japan and most European countries have seen their corporate bond markets developing in more recent decades (IMF, 2005). The size of an economy, the level of its development and state of financial architecture are some of the key determinants of the size of the corporate bond market. Although the US experience with corporate bond markets could serve as a useful model for Asian economies striving to develop domestic bond markets, they may find it difficult to emulate the US experience on account of differences in the level of financial development and experience. Even in the US, the corporate bond markets evolved over a long period of time due to a combination of regulatory intervention and market forces.

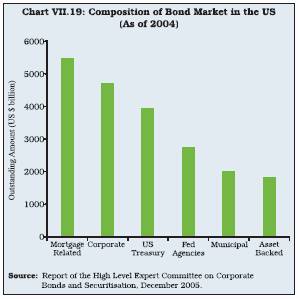

7.70 The growth of the corporate bond market in several countries, including the US and Korea, was spurred by increased availability of structured financial products such as mortgage and asset-backed securities. In the US, mortgage backed securities accounted for 26 per cent of the total outstanding debt in 2004, while the corporate debt securities accounted for 23 per cent of the outstanding debt (Chart VII.19). In a pure corporate debt market, only large companies can access the market. The availability of structured products provides an alternative way of addressing a fundamental limitation of the corporate bond market, namely the gap between the credit quality of bonds that investors would like to hold and the actual credit quality of potential borrowers (Gyntelberg and Remolana, 2006).

7.71 After the 1997 Asian crisis, several Asian economies have implemented measures to develop their local corporate bond markets to create multiple financing channels. The primary markets for corporate bonds in Asia have grown significantly in size. However, this growth in some cases has been driven mainly by quasi-Government issuers or issues with some kind of credit guarantee (BIS, 2006). The corporate debt markets are being accessed primarily by large firms as investors can easily assess their credit quality based on publicly available information. In Asian countries such as Malaysia and Korea, the primary corporate bond market is dominated by issues carrying ratings of single-A or above, with a large proportion of debt papers having triple-A ratings.

Box VII.3

Recommendations of the High Level Expert Committee on Corporate Debt and Securitisation

The key recommendations of the High Level Expert Committee on Corporate Debt and Securitisation, which submitted its report in December 2005, are summed up below:

Corporate Debt Market

Primary Market

1. The stamp duty on debt instruments be made uniform across all the States and linked to the tenor of securities.

2. To increase the issuer base, the time and cost for public issuance and the disclosure and listing requirements for private placements be reduced and made simpler. Banks be allowed to issue bonds of maturities of 5 year and above for ALM purpose, in addition to infrastructure sector bonds.

3. A suitable framework for market making be put in place.

4. The disclosure requirements be substantially abridged for listed companies. For unlisted companies, rating rationale should form the basis of listing. Companies that wish to make a public issue should be subjected to stringent disclosure requirements. The privately placed bonds should be listed within 7 days from the date of allotment, as in the case of public issues.

5. The role of debenture trustees should be strengthened. SEBI should encourage development of professional debenture trustee companies.

6. To reduce the relative cost of participation in the corporate bond market, the tax deduction at source (TDS) rule for corporate bonds should be brought at par with the government securities. Companies should pay interest and redemption amounts to the depository, which would then pass them on to the investors through ECS/warrants.

7.For widening investor base, the scope of investment by provident/pension/gratuity funds and insurance companies in corporate bonds should be enhanced. Retail investors should be encouraged to participate in the market through stock exchanges and mutual funds.

8. To create large floating stocks, the number of fresh issuances by a given corporate in a given time period should be limited. Any new issue should preferably be a reissue so that there are large stocks in any given issue and issuers should be encouraged to consolidate various existing issues into a few large issues, which can then serve as benchmarks.

9. A centralised database of all bonds issued by corporates be created. Enabling regulations for setting up platforms for non-competitive bidding and electronic bidding process for primary issuance of bonds should be created.

Secondary Market

1. The regulatory framework for a transparent and efficient secondary market for corporate bonds should be put in place by SEBI in a phased manner. To begin with, a trade reporting system for capturing information related to trading in corporate bonds and disseminating on a real time basis should be created. The market participants should report details of each transaction within a specified time period to the trade reporting system.

2. The clearing and settlement of trades should meet the standards set by IOSCO and global best practices. The clearing and settlement system should migrate within a reasonable timeframe from gross settlement to net settlement. The clearing and settlement agencies should be given access to the RTGS system. For improving secondary market trading, repos in corporate bonds be allowed.

3. An online order matching platform for corporate bonds should be set up by the stock exchanges or jointly by regulated institutions such as banks, financial institutions, mutual funds, insurance companies, etc. In the final stage of development, the trade reporting system could migrate to STP-enabled order matching system and net settlement.

4. The Committee also recommended: (i) reduction in shut period for corporate bonds; (ii) application of uniform coupon conventions such as, 30/360 day count convention as followed for government securities; (iii) reduction in minimum market lot from Rs.10 lakh to Rs.1 lakh, and (iv) introduction of exchange traded interest rate derivative products.

Securitised Debt Market

1. A consensus should evolve on the affordable rates and levels of stamp duty on debt assignment, pass-through certificates (PTCs) and security receipts (SRs) across States.

2. An explicit tax pass-through treatment to securitisation SPVs / Trust SPVs should be provided. Wholesale investors should be permitted to invest in and hold units of a close-ended passively managed mutual fund whose sole objective is to invest its funds in securitised paper. There should be no withholding tax on interest paid by the borrowers to the securitisation trust and on distributions made by the securitisation trust to its PTCs and/or SR holders.

3. PTCs and other securities issued by securitisation SPVs / Trust SPVs should be notified as “securities” under SCRA.